05 2007

Sous les yeux vigilants / Under the Watchful Eyes

On the international colonial exhibition in Paris 1931

Translated by Aileen Derieg

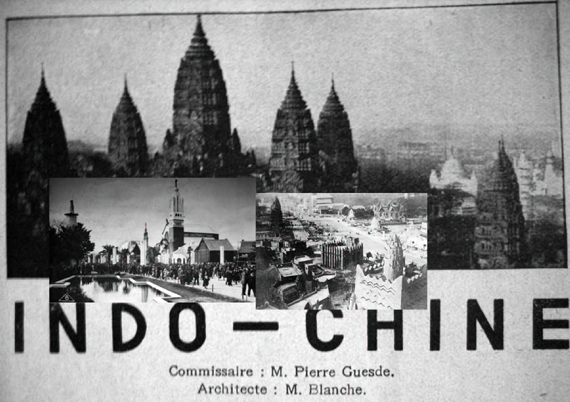

I would like to start with a photo. In the background it shows the reconstruction of the monumental temple of Angkor Wat for the “Exposition Coloniale Internationale” in Paris 1931; and in the foreground there is an artist sitting in front of his easel. All in white and wearing a sun hat, more à la casque coloniale than à la béret, he is about to transfer the cultural monument to a canvas in the western pleine-air manner under the scrutinizing and watchful eyes of two French policemen standing on either side of him. Angkor Wat, testimony to the decayed Khmer high culture of the 12th century – the original of which was a vine-covered ruin when it was “discovered” by Europeans in the mid-19th century –, was copied by the architects Charles and Gabriel Blanche in 1931 in Paris and protected – this was the gesture – from being forgotten, as it was linked with western art and placed under the watchful eye of the metropolitan police.[1] The reconstruction transcends the sanctum of an ancient civilization to become the “image of the five lands of the union [Indochina] that are joined together and strengthened through us.” “Cochin China, Cambodia, Annam, Tonkin and Laos, once peoples without any great political consistency” are allegorically symbolized by this encasement and gathered together into the exhibition section “Indochine”. On info displays in the interior spaces, modern French “Indochine” is presented with its achievements and developments. This is the bracket, with which the Asian foreign occupations were presented as parts of the French empire in the heart of this empire, in Paris.

Angkor Wat: Reconstruction in Paris 1931 – interior of the ‹Pavillon de l’Indochine› – ruins of Angkor Wat in Cambodia

In this picture, the police appear neither as a repressive power nor as an institution applying force. Instead they are shown as a curious and engaged institution helpfully assisting the construction and representation of an idea of “government” symbolized by the building of the temple of Angkor Wat. If we look at the place of the painter as an individual, functioning both as a recipient and as a productive multiplier of an idea of government in the process of construction, then the gaze of the policemen corresponds here completely to the place of a mediator between the entity of the state and the individual – in other words a citizen, who ideally governs himself. Yet what is the idea of colonial “government” in 1931, the concept of the “greater France”, the “Plus Grande France”, that was to be celebrated with this exhibition?

In an article for the opening, the “Commissaire général de l’Exposition Coloniale Internationale”, Maréchal Lyautey, compared that representation with the “Exposition de Casablanca” from 1915, which he had also organized: “But the exhibition of Casablanca was, on the whole, nothing but a war-machine. Yesterday, we inaugurated a great work of peace.”[2] What was new in 1931 were the self-referentiality of the colonial myth of progress and the signal: France intended to make peace with its colonial past by means of colonialism. The new lesson in modernity and citizenship, according to which individuals are to learn to regard themselves as part of a greater global community with common aims for progress[3], was formulated in the official exhibition guide for the section “Afrique occidentale française” with the words:

“Young people should learn all these names of people and places, the sounds of which may still seem strange to them today. In ten, twenty or thirty years, when these 14 million people, who are now still traversing untouched ground, are connected by railway tracks with our provinces in North Africa, when air travel reaches its full development, then these names will sound more familiar to our ears than those from the Provence or the Gascogne to the Parisians of the 17th century. / Then our Africa with its masses closely allied with us for defense and for prosperity will represent a magnificent and immediate continuation of our French humanity.”[4] Here France demonstrates itself as being capable of peacefully integrating or culturally assimilating people and regions, while developing and extending the position and participation of the “indigènes”. With different accents on assimilation or association, this model of a “colonisation de progrès” reached a high point with the exhibition of 1931. At the same time and in the striving for a “partnership” between the colonial population and the (political and economic) power of the metropolis, however, there were already signs the beginning of the demise of the colonial era as a whole. Designed as evidence of the “œuvre civilisatrice” of the “Plus Grande France”, the 1931 exhibition must be seen, not least of all, as a propaganda response to the upheaval and the increasing attempts to oppose the brutalities, humiliations and disfranchisements of colonialization with resistance and with national liberation endeavors.[5]

In the following I would like to take a closer look at the contradictions and ambivalences resulting within this government display of the “Plus Grande France” at the colonial exhibition. To do so, I will start with the 1500 “indigènes” that were hired and brought to France especially for the exhibition, who were supposed to “animate” the area of the exhibition dotted with various country pavilions. They performed dances, plays or military demonstrations, served in restaurants, sold goods at markets or demonstrated crafts.[6] Secondly, I will refer to a police dossier. It documents activities of the “indigènes” employed in the exhibition and others, who were categorized as anti-French.

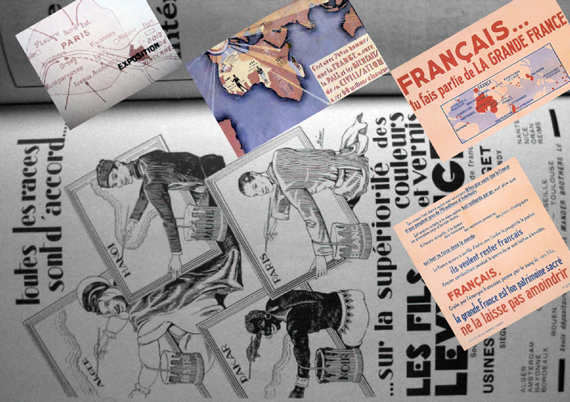

Let us begin, however, first with the exhibition as a cultural display of an appeal to a “Citoyenneté de la Plus Grande France”.

Mapping of the ‹Plus Grande France›: exhibition location in relation to the city – poster with world map for the Exposition Coloniale Internationale – appeal to the ‹Citoyens› – advertisement for artist paint from the ‹Guide officiel›

“indigènes” on display – un vivant réalisme “sous vos yeux”

Based on Foucault’s analysis of the prison, Tony Bennett develops a differentiated view of how the specific power display of the “exhibitionary complex” involved in the practice of “showing and telling” becomes a public event for the entire population in museums, exhibitions, trade shows and fairs. Following Bennett, in the “exhibitionary complex” the “population” functions less as an object of knowledge, but is instead appealed to as a subject that sees knowledge and its order, surveying and ideally inscribing itself into it.[7] In the 1931 exhibition the views, towers or raised points and gaze axes that Bennett describes as typical also play a central role. They enable transparency and overview for the looking crowd – on the one hand through the configuration of the exhibition staging, on the other through themselves and the social ties surrounding them. This kind of display of “scopic reciprocity”, in which the onlookers consciously become part of the show that their gazes follow, is suitable, according to Bennett, for regulating the crowd of onlookers through the co-presence with themselves and producing a new form of citizenship, in keeping with the Foucaultian concept of liberal governing. In this Bennett addresses the imperial function of the “exhibitionary complex” as a gaze axis, which highlights the “primitive” as counterpart, to emphasize all the more the rhetoric of progress.

View axes: excerpt from the ‹Guide officiel› with a view of Angkor Wat and Paris in the background – view of the bustling ‹avenue coloniale› – view from the ‹West Africa Tower› of the ‹avenue coloniale›

At first glance, the colonial exhibition described here might appear to be an example of this kind of imperial exhibition display, especially with the live presence of “indigènes” – but only at first glance, I think. In fact, Bennett’s attention is focused largely on the self-relation of the audience of the exhibition – and not, for instance, on the relationship between the looking crowd and the viewed objects/subjects. These remain immutable in his description, even “dead” objects that are denied any power of action. If we look, in comparison, at contemporary debates, fears and conflicts about the presentation of the “indigènes”, then it becomes clear that this kind of imperialist gaze regime, operating through binarity, not only does not always remain the same and unchanged, but was also controversial. When it became known, for instance, that there was a plan to have “Indochinese” workers pull visitors through the grounds in rickshaws, there were protests from the so-called “Comité de Lutte des Indochinois contre l’Exposition Coloniale et les massacres en Indochine” [sic!]. In the end, however, the offers for “transport intérieur” included not only rickshaws, but also a small train, camels and the “pirogue”. Visitors to the section “Togo-Cameroun” could have themselves be rowed around on Lac Daumesnil and then buy a drink with genuine ingredients from the colony. The invitation was formulated as an appeal to confidence and promised an incorporation: “Entrust yourself to the tough dugout rowers of the Wouri River of Douala. Drink coffee and cocoa from the plantations there. In this way, you will enrich your newly acquired insights with a physical and specific source.”[8] Both literally and metaphorically, the exhibition stressed what was embodied and experienced, as seen for instance in the central role of the “restaurants éxotiques”. Unlike in earlier colonial exhibitions exposed to vehement criticism, here the “indigènes” were to appear as “authentic contact persons”. Instead of being reduced to the position of exhibition pieces, they were to be accessible and responsive, in order to give visitors the feeling of traveling around the world and having everyday experiences with the various peoples. Hence the display corresponded to a kind of “vivant réalisme”, a tableau in which the “indigènes” moved in the same crowd as the stream of visitors; people could interact and should take part, for instance, in bartering. At the same time, a high value was placed on modern and “tasteful” relations between the audience and the “indigènes on display”. The address to the visitors in the Guide officiel gave ample space to an educational request for appropriate behavior:

“[…] here you will find no exploitation of the base instincts of the common public. […] Marschall Lyautey and with him General Governor Olivier along with all their staff consider you, honored visitor, as a person of style. There will be none of those Bamboula Fetes, those belly dances and market hawking that have already ruined the reputation of several colonial events […].

These people’s way of living is moving closer to your own today than you think. Turn your attention to their work. Watch how they operate. […] People communicate not only through words; impressions are not limited only to sight. […]

Colonizing today means: trading with ideas and words, by no means with existences burdened by physical and moral misery, but rather with free and happy people with purchasing power.

A word of advice: in view of all the foreign or domestic presentations, do not laugh at things and people you do not immediately understand. […]. The presentations of other people often correspond to your own, but are simply expressed differently. Think about this. May a cultivated and highly French joy animate you, honored visitor […].”

In keeping with the impressions that this quotation may initially convey to us today, with the way it directs attention to oneself and the “indigènes” one is presented with, in Bennett’s description of the imperialistic function of the “exhibitionary complex” the audience is implicitly presumed to be European – a gaze direction, however, that I would like to complicate now for the sociality in Paris around 1931:

It has been passed on in letters, for instance, that the later Sengalese state president and poet Léopold Senghor, who was in Paris as a student around this time, discussed and criticized the exhibition with his fellow students. It may thus be presumed that he and his friends mingled among the crowd, who observed the miniature display of “Plus Grande France” with a self-reflexive view from the side of power – in other words with the male eye of metropolitan power – as an appeal to the “Citoyenneté”.[9]

A photograph from the perspective of the self-reflexive gaze at the crowd also provides evidence not only that the “indigènes” were visible here, but also of the dubiousness of a sharp distinction between visitors and “indigènes”, in other words performers. The organizers sought to clarify this by forbidding “indigènes on display” to appear in western clothing – except in the rare case that specifically the inappropriateness of “indigènes en travesti” was to be depicted. Nevertheless, however, according to reports there were some unpleasant incidents, for instance with “indigènes” – security guards. Visitors were said to have frequently requested them to light their cigarettes or even to have tried to take away their bayonets. In a letter of protest to Lyautey, Candace, a member of parliament from Guadeloupe, criticized the “brutalities used against black visitors to the exhibition” by the “French” – probably white – security guards. As background for this kind of complicated configuration in social relations and in the reading of difference between the subjects of the empire and the exhibited objects from the colonies, the historian Pascal Blanchard also supplies a number: 120,000 to 150,000 migrants from the “overseas territories” had already settled between Paris and its suburbs at this time.[10]

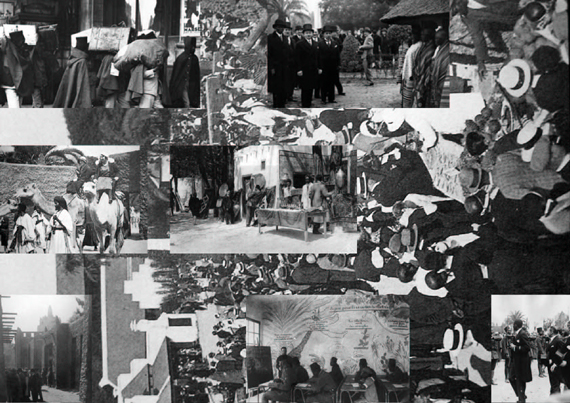

‹un vivant réalisme›: In the background the view of a street with a crowd at the Exposition Coloniale Internationale 1931 – arrival of the ‹troupes coloniales› – exhibition opening with the Colonial Minister Paul Reynaud; the other people visible in the picture are obviously less well known – visitors riding camels – the Tunisian souk – the so-called Sudanese road – ‹instruction des illêttrés›, marksmen of the Senegalese troop learning French within the exhibition display – exhibition opening with Blaise Diagne

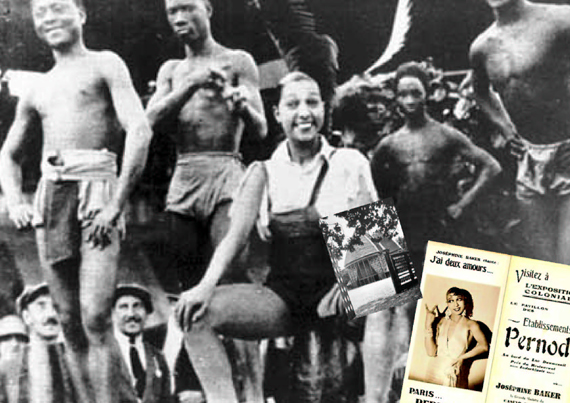

The diversified differences – at the level of the exhibition display itself as well as at the level of the onlooking sociality – cannot in any way, however, be regarded as some kind of preliminary exercises for an anti-colonial display. On the scale of colonial imagery, this is perhaps most glaringly evident in the role of Josephine Baker: the black US American artist appeared at the colonial exhibition under the name “Queen of the Colonies” – despite protests from people who scoffed that the USA could hardly be regarded as a French colony. The fact that the colonial spectacle of the exhibition was not always entirely particular about truthfulness and authenticity is by no means hidden in the official publications. Indeed, the hybrid stagings of the exhibition display appear there more in the nostalgic light of a celebrated spectacle of difference than of a “colonial culture”, which has already been subjected to the loss of its primalness and originality due to the project of the “Plus Grande France”. The “guide officiel” says about the pavillions of the section “Togo-Cameroun”, for example: “These territories are represented here by numerous buildings of various sizes, which form pavilions. Here these are huts of chiefs and natives of Bamoun, located in Cameroon at the edge of the forest and the northern savanna. The huts have naturally been stylized by French architects.”[11]

‹Coloniale culture›: Josephine Baker as ‹Queen of the Colonies› with her troop at the Exposition Coloniale 1931 – Pernod advertisement with Josephine Baker and her song ‹J’ai deux amours...› for the 1931 exhibition – ‹Pavillon Togo-Cameroun›

looks

In contrast to historically earlier examples, in her description of the “indigènes” exhibited in 1931, Elizabeth Ezra accentuates the objective of this representation as an idea that it evoked among the audience: the onlookers supposedly thought that the people they were watching did not know they were being observed. Ezra derives this supposition from contemporary commentaries, which emphasize that the “indigènes” in the “tableaux vivants” looked and acted as though they were not aware of the presence of the exhibition and its viewers, but carried out their activities absorbed in their “life world”.[12] In this voyeuristic fantasy, the “indigènes” cast no return glance, the place as subjects of their own gaze is obstructed for them. In fact, however, this contradicts many existing photographs, which do not at all convey the impression that people are doing things there that they would be doing anyway. Instead, they seem to suggest to me the interpretation that the depicted “indigènes on display” are not dancing or selling something or fabricating crafts as much as producing a representation of work and activities within the colonial display that positions them. Their appearance might thus be said to correspond more to the endeavor of depicting “work” and a position “as indigène” in a certain way, appearing for the duration of the exhibition in a specific manner as “indigène-actor”, additionally carrying out a kind of animation work with the visitors. This would mean that those involved subjectivate themselves self-reflexively in the required exhibitionism, working with the “spectacular display” and their positioning as attractions.

The emphasized non-interaction between audience and “indigènes on display” is probably less a negotiation of what happened in terms of social practices and identifications at the colonial exhibition than that which Ezra grasps in reference to Bennett as gaze relation in the symbolic order. At the same time, there exists “no possibility of symbolic reciprocity”, “when the object of the gaze is not (the same as) the subject, when instead, it is subjected to the gaze. (I say no possibility of symbolic reciprocity because, although there is nothing preventing the objects of such a gaze from looking back, their spectatorship would nonetheless not result in their ‘seeing themselves from the side of power’.)”[13] The seemingly immovable boundary between the colonized and the colonizers, between the observers and the observed that was to be drawn, reinforced and, most of all, discursively maintained was naturally perforated in the everyday and resistive practices around the exhibition by a “return gaze”. However, within the “exhibitionary display” these gazes are neither represented nor representable: in order to see the articulation of a subjectivization through the gaze as “indigène on display” and possibly simultaneously as “indigène” audience, we must leave or complicate the framework of the assumptions of a cultural politics and observation within the governmentality discourse surrounding the “exhibitionary complex”. I would like to turn now to further aspects of the exhibition display: the dossiers of the secret police C.A.I.

Looks: ambulant merchants with visitors

Secret Gaze

In the archive of the former colonial ministry there are 81.8 meters of files with reports from the “Service de liaison avec les originaires des territoires français d’outre-mer” (“Liaison service with those living in the French overseas territories”), abbreviated as S.L.O.T.F.O.M. This corpus covers the period between 1915 and 1957 and also contains files from the C.A.I. – “Service de Contrôle et d’assistance des indigènes des colonies françaises” (“Service for the control and aid of the natives of the French colonies”) – the predecessor of the S.L.O.T.F.O.M. The C.A.I. was a small special secret police under the supervision of the military direction and led by the general inspector of the “Indochinese” troops, which was established in 1923. It succeeded a service that had been instituted by the ministry of war in 1916 to “oversee and organize the colonial workers in France”[14] and to ascertain the need for “indigènes workers”. Following an interministerial agreement, the service transferred in 1917 from the ministry of war to the colonial ministry. The C.A.I. employed agents provocateurs and undercover informants from diverse milieus, monitored individual “indigènes anti-français”, their movements, newspapers and organizations, and worked closely together with the ministry of the interior and with the general French police.[15]

These files are rare testimonies to the activities of “indigènes”. They are a find for the history of the organization of emerging nationalist and communist movements in the colonies and in France, and they contain a substantial amount of material about resistance against the “Exposition Coloniale Internationale” of 1931. Even though the anti-colonial movements were still dispersed, marginal and largely operating in the underground at that time, this material marks a historical point where the confrontations coalesced into activity that threatened the French colonial establishment. A surveillance network is evident especially for the “Indochinese” section of the exhibition, which heavily enclosed the so-called “cité indigène”. Without special permission the “indigènes on display” were not allowed to leave the exhibition grounds and the country pavilions in which they were accommodated. This was intended to forestall making any contact with overseas migrants in Paris. On 24 July 1931, Pierre Guesde, the “commissaire du gouvernement générale de l’Indochine à l’Exposition” wrote to the colonial ministry: “Grouped as they are now, in a relatively restricted space surrounded by a barrier, the surveillance and control of their activities is obviously much easier and more efficient than if they had been scattered all over the place. Then they would have escaped from us entirely and become an easy target for the propagandists.”[16]

The Vietnamese community in the Quartier Latin near the exhibition grounds was also under special surveillance by the C.A.I. There are accounts, for instance, that a report about a meeting was passed on to the police commissioner for the section “Indochina”, where a protest on the evening before the opening was planned and another day of action was discussed: immediately after the exhibition opening “anti-imperialist stickers” were to be spread around the grounds and “balloons with red flags” released into the air. On the evening before that, 33 Annamites, two of which were not students, were already arrested leaving a meeting of the “Indochinese Communist Party”, which had sent out a call for resistance against the exhibition, in the cellar of a restaurant in the Quartier Latin.

Most larger-scale actions were prevented by repressive measures, and for this reason are frequently only evident in the denunciation documents of the C.A.I. However, several organizing and action attempts failed because of their political conception, such as that of 12 April: ten “Indochinese” activists allegedly boarded a ship in Marseilles and attempted to agitate among the “indigènes” hired for the Paris exhibition who had just landed, and to move them to strike, whereby they were assured of support from the Communist Party. However, the new arrivals rejected these ideas and reported them to their supervisors. The C.A.I. also registered movements on the grounds of the exhibition: one file reports on a meeting between members of the “Étoile nord-africaine”[17] and musicians from the exhibition. There is a report about a wave of dismissals in the “restaurant indochinois”: the wife of Sai Van Hoa, one of the leaders of the radical student group “Association d’Enseignement mutuel”, had a job there in the cloakroom and was said to have smuggled anti-colonial propaganda into the exhibition grounds. The same was said about the cook there. Another report noted the sudden and presumably politically motivated departure of 23 musicians from a hired North African band. In the course of the organizing attempts against the exhibition, in addition to numerous arrests, there was also a wave of involuntary departures: on 22 May Nguyen Van Tao, whom Herman Lebovics calls the hero of the C.A.I. files, was deported along with a number of others.

The C.A.I. files also prove to be an archive of flyers, posters and similar protest material. For instance, a poster produced by the “Ligue de défense de la race nègre”, which was found on the outside walls of a school near the colonial exhibition, is preserved there. It condemns the recent incarcerations and shootings of women from Cameroon, who protested against high taxation.

The Annamite activists, partly supported by the “Ligue anti-impérialiste”[18], were probably the best coordinated group, active in Toulouse, Marseilles and Paris. One of their successful interventions was to persuade the “indigènes on display” from the section “Indochine” to refuse to carry a huge dragon around the exhibition grounds. Consequently, the exhibition organizers found themselves compelled to entrust this task to Africans. However, there were not only political contacts and attempted alliances between the “indigènes on display” and their compatriots, who were already living in France, many of whom were students. There was also a coordination meeting between “two Indochinese, one Japanese, one Korean, and one Negro” that was uncovered by the C.A.I. In September, a certain “Joe” operating within the exhibition denounced the plan of the “Ligue de défense de la race nègre” to tear down the statue of Khai Dinh in front of the Annamite Pavillion. The same plan of action was reported by “Désirée”, who was charged with observations outside the exhibition, and by the C.A.I. agent “Guillaume”, about whom nothing else is known. It is likely that the calls from the “Parti communiste français” were addressed more to the working class of the “francais de souche”, the white majority population, to see themselves as allies of the colonized. This also applies to the “Véritable Guide de l’Éxposition Coloniale: L’oeuvre civilisatrice de la France magnifiée en quelques pages” from the same source, which the C.A.I. found in the Tunisian restaurant and in the “pavillon des forces d’outre-mer” as well.

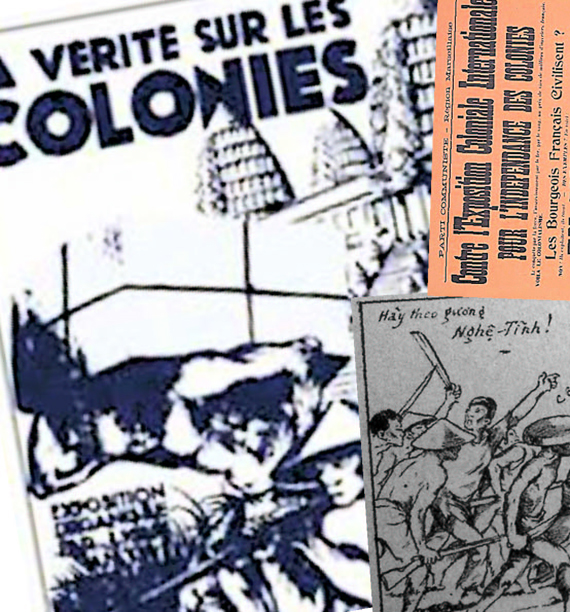

C.A.I. archive: protest material

a new war machine

A look at these police files makes public the protests and unions that were concurrent with the successful large-scale event of the colonial exhibition, which drew an early and fundamental rift through the “fracture coloniale”. The colony, previously located in an “elsewhere”, with “indigènes” drawn as different from the progress and modernity of the metropolis in terms of both time and geography, is manifested through the view of the panorama of various protests surrounding the project of 1931 as having arrived within the metropolis. Yet what kind of a subsequent reflexion does this knowledge leave on the display of the exhibition?

Even though the exhibition already presented itself ambivalently as the manifestation of a comprehensively universalist, republicanly modern and progressively integrative “Plus Grande France” with colonially graded rights and concepts of social participation[19], in the context of the anti-colonial protests and in taking the C.A.I. files into account, its subsequent interpretation cannot be to reduce it to an “exhibitionary display”. The relevance of Bennett’s project of reading the history of the museum in a culturalizing tendency reaches its limits here. Through the figure of placing the C.A.I. files as a display side by side with the exhibition display, I propose not reading the latter only within the cultural discourse with its ambivalences of a “colonial culture on display”. In fact, I argue for an inseparability of that which Elizabeth Ezra called “French colonialism” (in the sense of a distinct “colonial culture”) contrary to French “colonization” (in the sense of a form of “political and economic dominance”).[20]

Ezra regards the 1931 exhibition as an example of “French colonialism”, which she relates to Homi Bhabha’s well known ideas on “colonial mimicry” (the wish and the ambivalence of a subject of difference, which is almost the same, but not quite). Bhabha’s interest here is in whether and how colonial ambivalence grounded in indistinguishability as the discursive condition of dominance, could be turned into a motive of intervention, of the rebellious counter-objection. Ezra rejects this idea, however, with the argument that precisely the “doubleness” of the French colonial discourse of the “Plus Grande France” supplied “a sort of reverse doublure”. She maintains that this is a facing, which does not undermine the colonial discourse, but rather protects, fortifies and reinforces it from the outside. She emphasizes that colonial ambivalence has neither enabled nor prevented resistance. The French empire did not destroy itself, but was instead overcome. According to Ezra it is an unconsciously imperialist gesture to locate the possibility of subversion within the colonial discourse. A gesture of this kind colonizes the resistance itself and thus makes it accessible and appropriate to the position of the colonizer. In her view, colonial ambivalence is more suitable for undermining the active role of subjects who have, in fact, resisted.

Here I do not wish to support or reject either Bhabha’s or Ezra’s argumentation, but instead to simply emphasize that, as it appears to me, the protests that have been passed on intervene to avert exactly these discursive ambivalences: through spreading counter-information about facts and events in the colonies, for instance, which the publicness of the displays were intended to cover up; or in the way that the “return gaze” at the fantasies of exoticized “indigènes on display” placed in a submissive situation were to be made manifest and publicly fixed. On the other hand, although the protests actually operated as being situated within colonial ambivalence, they consistently sought to join with other places in it. In this case, the attempts to organize between the “indigénat” in migration and in temporary working stays in the exhibition appear to me to be central. The protests thus cross the ambivalences in multiple ways and expose them as contradictions of a binary apparatus. They provide clear evidence of the goal of conjoining socially segregated sectors and discourses with one another. Separately and differently governed places in “Plus Grande France” are thus crossed with new coalitions: the Quartier Latin is connected with the exhibition grounds, the colony with the metropolis, politics with culture, and the picturesque, the objectification of the “indigènes on display” with intellectualism and communism.

At every position, the protests reject the barriers drawn between the “metropolitans” and the “indigénat”. In relation to the exhibition, it might be said that this practice represents an attempt to bring the societal “prison display” within the “exhibitionary display” into public negotiation and visibility. I prefer to read these acts of resistance as a practice of embodied experience as self-reflexive visitors and simultaneously as performing workers within the colonial culture of the exhibition. They are neither completely inherent to the discursive ambivalence of “Plus Grande France”, nor are they its paradoxical external effect. Instead, they begin to form a war machine exactly where Lyautey’s large-scale project wanted to make peace.

Many thanks to Daniel Weiss

Literature:

1931-2006. 75 ans après, regard sur l’exposition coloniale de 1931; Dossier on the series of events of the marie of the 12th Arrondissement, Paris, http://www.mairie12.paris.fr/index.php/mairie12/documents.php?id=3561, accessed: February 2007.

Bennett, Tony, The Birth of the Museum. History, Theory, Politics, London 1995.

Exposition Coloniale Internationale, Paris 1931, Guide officiel.

Ezra, Elizabeth, The Colonial Unconscious. Race and Culture in Interwar France, Ithaca/London 2000.

Guide complet et illustré. Exposition Coloniale Internationale Paris 1931

commenté par Paul Roue; http://www.jetons-monnaie.net/p/expo1931.html, accessed: February 2007.

Hodeir, Catherine et Pierre, Michel, L’Exposition Coloniale, Paris 1991.

Lebovics, Herman, True France. The Wars over Cultural Identity 1900–1945, Ithaca/ London 1992.

Morton, Patricia A., Hybrid Modernities. Architecture and Representation at the 1931 Colonial Exposition, Paris, Cambridge/London 2000.

Promenades à travers l’Exposition Coloniale Internationale, Paris 1931, 24 Cartes Détachables.

http://www.zoohumain.com/ index.php

[1] Claude Farrère explains this gesture in L’Illustration with the grand words: “[…] I place my hope in the wisdom of good reason, that we as the occidental peacemakers represent the legitimate heirs of this ancient Khmer civilization and certainly better than all that followed until the day of our landing on these remote and sacred shores. There, where we find ourselves, we have undertaken to prevent man from murdering his fellow man and destroying the past, this natural predecessor of the future. It is a successful undertaking. Let us continue it!” (cf. Hodeir/Pierre 1991, p. 24).

[2] L’Illustration, 23. Mai 1931, quoted from Ezra 2000, p. 17 f.

[3] Plus grande France at the time of the exhibition comprised a territory of 10 million km2, “an empire with a population of 100 million”, as various contemporary sources emphasize – of which 40 million were French citizens.

[4] Guide officiel, p. 68

[5] During the Rif War of 1925, many French leftists expressed solidarity with the Moroccan rebels and mobilized against colonialism. “L’étoile nord-africaine”, predecessor of the Algerian liberation movement, was founded in 1926 in France and attracted members especially from the Algerian workers in the Parisian Banlieue. In February 1930 the “Indochinese Communist Party” was founded in Hong Kong; in the same year there were numerous anti-French revolts in Algeria and “Indochina”, which were brutally suppressed. Under the name “Néo-Destour” the Tunisian nationalist movement initiated campaigns to boycott French products in the 1930s. 1930 was also the year of the first major wave of the deportation of politically active Annamese students from France.

[6] According to the Guide complet et illustré from the exhibition organization, approximately 1,000.- Francs per month were paid as wages to “each of the indigènes performing there”.

[7] Bennett 1995, p. 51–69.

[8] Guide officiel, p. 107.

[9] Lebovics 1992, p. 92.

[10] The “Union intercoloniale”, for instance, was founded as early as 1922, in which residents from the colonies organized themselves in France.

[11] Guide officiel, p. 105.

[12] Cf. Ezra 2000, p. 31.

[13] Ezra, 2000, p. 32 f.

[14] “Archives nationales”, accessible at: http://caom.archivesnationales.culture.gouv.fr/sdx/pl/doc-tdm.xsp?id=FRDAFANCAOM

_EDF046_slotfom&fmt=tab&base=fa&root=FRDAFANCAOM_EDF046&n=&qid=&ss=true&as=&ai=, February 2007.

[15]From 1939 onward, the activities of the C.A.I. were limited to monitoring certain individuals and issuing identity cards that allowed people from overseas to circulate in the metropolis. In 1941 it was renamed as “Service coloniale de contrôle des indigènes”, in 1946 as “S.L.O.T.F.O.M.”. After World War II this police seems to have increasingly lost its significance.

[16] From the C.A.I. files, quoted from Ezra 2000, p. 24.

[17] Together with the “Ligue de la défense de la race nègre” and the “Parti annamite de l’indépendence”, the “Étoile nord-africaine” were in coordinated contact with the “Comission coloniale”, a committee of the Communist Party of France to support activists in the colonies. The C.A.I. devoted particular attention to the “danger of infection” with Bolshevist ideas. Accordingly, material is also found in the C.A.I. files about the PCF and the Surrealists that worked together with them. (cf. FN 18)

[18] The communist “Ligue anti-impérialiste” was founded in 1927 as an international group that was intended to coordinate the national emancipation movements with the workers movements in the imperialist and colonized countries. In conjunction with the PCF and sympathizers among the Surrealists, the “Ligue anti-impérialiste” realized a counter-exhibition from 20 Sept. to 2 Dec. 1931 entitled “la verité sur les colonies”. It drew a total of about 4200 visitors – in comparison with the 33 million tickets sold for the “Exposition Coloniale Internationale”!

[19] In the French colonies different instances of government applied respectively to the “indigènes” and colonial population, and the application of laws differed in the same way. Civil rights were only granted in the “old” colonies – Antilles, Guyana, Ile de la Réunion or the four “Communes” of Sénégal.

[20]Ezra 2000, p. 2.