03 2018

Barrial Geographic

Technecology and parody in practices of resistance against gentrification in Lagunillas (Málaga)

Translated by Kelly Mulvaney

Lagunillas in the face of the ‘centre’ dispositive

Despite its continued operation, the brand Costa del Sol through which Málaga was offered to beach-and-sun tourism during the Francoist dictatorship has become saturated, overexploited and too dependent on the excesses of the industry of financial real estate. But once the real estate bubble burst in the first decade of the twenty-first century, the capital of touristic real estate is being swiftly reorganized in order to inflate another bubble, this time through the idea of culture. The historical centre of Málaga has become a great outdoor mall, redesigned under the sign of ‘the cultural’ as touristic bait made to profit foreign investors and the conservative political and business groups of the city. Culture and Urbanism have allied in order to make Málaga a ‘cultural city’ through both the proliferation of museums and the commercial use ad nauseam of the Picasso brand.

During the last years, the cultural branding has extended its borders towards the urban and the cool by contracting artists such as Obey or Invader to create authentic artistic installations, colonizing neighbourhoods and emblematic zones of the city and blowing air into the bubble of touristic real estate. This has taken place at the request of the municipal neoconservative group, while official institutions have abandoned local creators to the background.

Ironically, in the age of the cultural branding, the centre of the city doesn’t refer to a territory geographically delimited by historical sediments that have been turned into heritage, as much as to an expansive and mobile capitalist form of life. Like money itself, which lost the material reference to gold, the centre progressively loses and dissolves the material references of time (history) in favour of the appropriation of space (geography). Thus, the centre becomes a mobile dispositive that moves to the beat of touristic curiosity (either captured or over-produced) and the urbanistic reforms and speculative interests that accompany it. As spaces are consumed, places are vacated of memory and singularity.

As a dispositive, the centre activates and deactivates forms of life according to the flow of capital, producing what Suely Rolnik has called lux subjectivities (luxo) and trash subjectivities (lixo). This has multiple spatial expressions and consequences for the local people: the trend to polarization of rich and battling for urban space; the displacement of neighbours from the centre’s neighbourhoods as gentrification occurs around tourist accommodations; the exoticization, over-representation and substitution of all types of local cultural codes and practices; the isomorphism franchises and multinational corporations; price increases; precarious jobs...

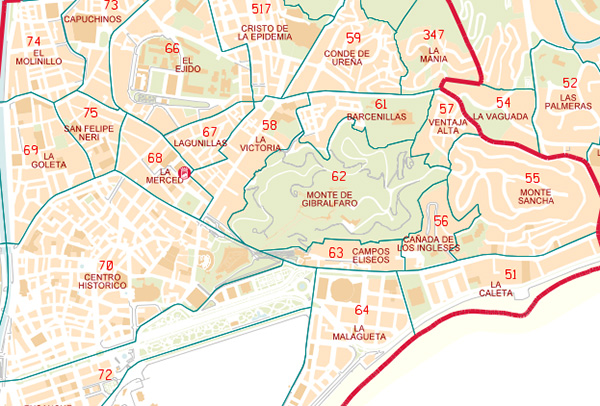

The neighbourhood of Lagunillas is located at the margin of the current ‘centre’ dispositive. It moved from being one of its borders into the new radius of speculative interest: today Lagunillas is being called to become centre. Lagunillas is a network of streets with low-rise houses located in the flat area between two urban hills. It has maintained a certain village look, and it was home to a prosperity and commercial activity until the first half of twentieth century that, in the second half of that century, was left behind.

Lagunillas is located parallel to Cruz Verde, a neighbourhood degraded and pounded by heroin during the 1980s, and where in the 1990s the Andalusian state and local governments implemented a policy of concentration and rehousing for families displaced from Roma shanty towns and for families dispossessed by the 1989 floods. Despite the intention to bring them closer to the centre, neither the problems nor the violence that often surround the survival strategies of poor and stigmatized people were made to disappear by concentrating them into a building of carceral design and other buildings along Cruz Verde street. On the contrary, aesthetics and situations of marginality extended around the zone and Lagunillas became assimilated under the effects of the poverty concentration-and-control politics that Cruz Verde had come to signify.

Thus, Lagunillas gained an image of abandonment, full of closed establishments, eroded facades, empty lots and accumulated rubbish and dirt, in addition to a host of social problems derived from poor housing and unemployment. It received institutional treatment as a ‘marginal neighbourhood’ and the area was re-named ‘Cruz Verde-Lagunillas’ in the official classification of neighbourhoods of the historic centre. Thanks to some local shops (most of them now displaced by big malls) and the associative, welfare-oriented fabric of the neighbourhood it was able to stay alive and become enriched culturally and socially in the first decade of the twenty-first century, as activities were organized, including a project to beautify the facades and streets with children, and press reports, amongst other things.

But in recent years Lagunillas has been undergoing, as we put it, resignification: from a degraded and dangerous neighbourhood to one worthy of touristic attention, especially thanks to the graffiti artworks that fill its facades, made for no pay by local graffiti artists and visiting friends. Slowly, many erstwhile owners have sold their properties and touristic and AirB&B apartments have appeared. Groups of young tourists already compose with the visual landscape as the noise of rolling suitcases composes the soundscape. At the same time, Northern European real estate companies encourage small traders and neighbours to sell by slipping flyers under every door. Step by step, politics creates an economy of opportunism in the neighbourhood that threatens to expel the remaining inhabitants and their singular form of life. The most recent urban plan holds that the centre, the profitable area, must extend towards Lagunillas and leave the currently unassimilable Cruz Verde alone as the new border, which also makes it a potential ally as a neighbourhood affected by gentrification.

Nevertheless, not only tourists and opportunists but also creators and activists have appeared in the Lagunillas neighbourhood composition. Or maybe, it would be more precise to say with Deleuze, the neighbourhood is engaging in a revolutionary becoming at the same time that activists, artists and sympathizers are creating a neighbourly becoming.

During the 2016 Christmas season local creators and sympathizers occupied a plot of land where cars had been parking. They gardened, beautified it, and called it ‘Victoria, ¿de quién?’[1]. In a short time a neighbour created the association ‘Lagunillas por venir’ and assembled a large portion of the neighbours to organize self-defence and mutual support. Different recreational activities were carried out at the Plaza de la Esperanza (jazz concerts, open air fair with tombola, etc.). A short film cycle called ‘Lagunillas se defiende: luchas vecinales y gentrificación’[2] was organized at the recovered plot during the allegedly glamorous Málaga Film Festival. And expression machines such as Lagunews[3] were created, that is, a video news program broadcast on YouTube, which shows the neighbourhood degradation in opposition to the ineptitude, sloppiness, opportunism and hypocrisy of the local leaders and brings out Lagunillas’ singularity in the humour, irony and parody characteristic of its neighbours.

Lagunews: technecologies or the laughter of the neighbourhood

Where the urban and cultural policies of the city point towards a kind of tourism and constituency seduced by the aesthetics of glamour and luxury, Lagunews, the local news of Lagunillas, is situated in the aesthetics of accumulated trash, rubble, dog shit, cracks on the walls, abandoned stores, dumpiness, austerity of the urban furniture, the freaky, “chav” and ‘merdellón’ thing[4].

The anchors of the news also express this luxo/lixo duality. They are two foam rubber puppets operated from behind, named Lagunillas Von Bismarck and Belén Esteban. The first, which parodies the figure of Gunilla Von Bismarck (the ‘throneless queen’ of the jet set of Marbella) with a German accent and a wide-brimmed sun hat, represents the glamorous and “high culture” face to which the designers of Málaga’s image aspire (just think of the Thyssen Baroness Museum, the Harbour 1 reform that imitates the super-exclusive Marbella’s Puerto Banús, the use of Antonio Banderas to support events, projects and museums, etc.). The second, Belén Esteban, represents a media personality from the “low culture” or “merdellón culture”, joined the media show through a relationship with a famous bullfighter and became a national yellow press icon because of her capacity to provoke controversy, her husky voice, her shouts, her rude language… that is, thanks to her spectacularized lower-class performance. In fact, Lagunews reflects the bipolar background of the touristic and museumified Málaga, which relates to the composition of any yellow TV show where the aristocratic and the chav, the luxury and the trash, mutually need, meet, and hide each other.

The creation of technodispositives like Lagunews is not so much premised on an instrumental-technological reason to reach mediactivist goals, in the sense of an information alternative to mainstream media. It is not an instrument through which people assert or oppose truths in an argumentative or representational mode. It is rather one of the shapes taken by the neighbourhood-making of the neighbourhood. Through the use of irony, parody and theatre, it is one of the enunciation assemblages through which their inhabitants subsist, singularize themselves, and produce common notions and joyful affects. And then they make them circulate throughout the net as contagious connectors. More than media, Lagunews is a mode of enunciation that shows “a surplus of desire manifested that could not be explained only by technical utility”[5]. It is a technecological expression of the neighbourhood, where technology transversalizes with the desiring-flow in Lagunillas’ revolutionary becoming. Lagunews is a neighbourhood-making that crystallizes in the web as a subproduct not only of a multiple and situated knowledge, but as a wink. It is a form taken by both critique and the embodied laughter of neighbourhood-making in resistance practices.

‘Barrial Geographic’: when the neighbourhood observes the consumer gaze

End of July 2017. A local newspaper devotes one page to promote the initiative of a local business run by an entrepreneur specialized in territorial planning, urbanism, and real estate. It’s a promotional page, but presented as news. The newspaper advertises a guided tour around Lagunillas’ graffiti led by a young art historian “expert” on the topic. It costs 8€ per visitor. There are 30 people listed. Two weeks before some of the neighbours tried to contact them. No answer. They are required to contact the Association in their event on Facebook. No answer. Two days before one neighbour gets to talk to the entrepreneur, who tells him that the street is free so they will do whatever they please?

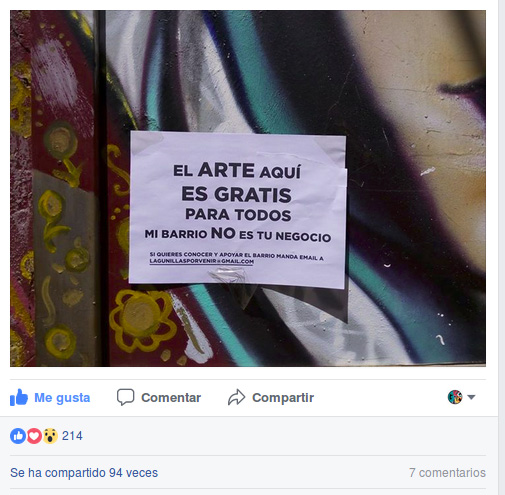

‘Ok, will do so too’, we thought. Graffiti artists got pissed off. ‘So they are gonna charge for showing the graffiti we’ve made for free and for everybody!?, So they are gonna explain our creations without taking us into account!?’. A necessary debate arose then about the content of the graffiti: until that moment, topics had not referred to the neighbourhood’s situation, they were not presenting any conflict for gentrifying agents, and even more, they were being claimed. Artwork destruction by artists like Blu and other street artists in Berlin were brought to mind[6]. Despite the fact that this debate remains to be explored in more depth, graffiti artists started to take the role they might be playing for the new cultural-real-estate bubble more seriously. A few weeks later the walls started to babble a critique. For the first time some graffiti artists started to rise up against the perverse consequences of massive tourism and capitalist opportunism, which makes Lagunillas a more uncomfortable or problematic “asset” in the context of Málaga[7].

We decided to become active. Two days before the date we gathered around the proposal of transforming the visitor group into the object of our sight, curiosity, and study. All this was happening in the context of a media attack across Spain to the increasingly visible resistance of neighbours all over Spain to tourist overcrowding and its consequences. During those days only two words could be heard on the Spanish media: ‘Venezuela’ y ‘turismofobia’. The word turismofobia was launched throughout TV, radio, paper and Internet. There are whole talk shows devoted to spread a term created by the media-financial-touristic dispositive in order to pathologise and depoliticise ongoing expressions of the discomfort the tourist-real-estate industry is bringing about over the local lives[8]. We had to take the possibility of being pathologised and criminalised into account.

The first step was to use the graffiti to directly interpellate both the business and the assistants. We decided to post the message ‘Art here is for free. For everybody. My neighbourhood is not your business. If you want to know and support the neighbourhood send an email to lagunillasporvenir@gmail.com’. Thereby, beyond the uncomfortable feeling and the invitation to know the neighbourhood with the neighbours, the message would be registered in every photograph.

The second step was to use the opportunity to film a Lagunews episode, inverting the relation of capture by integrating the tourist business as an extra into our creative practice.

And for the third step, the language of humour and parody, aside from being the “spontaneous” language of the neighbourhood, took on a special strategic importance. Parody has a double sense: in opposition, taken like a mockery, and in parallel, as repetition that introduces a difference. Mixing Bourdieu with Butler, it was about responding the cultural-touristic habitus with a queer anti-gentrifying parody. Parody allowed us to situate in parallel to the predictable liturgy of a guided touristic group and to introduce a difference, to produce an event and singularise ourselves in the face of the capitalist instrumentalization of the neighbourhood’s cultural wealth. The guided tour was a performative act through which graffiti in Lagunillas would begin to be instituted as an art commodity and object of expert knowledge, the neighbourhood as museum, the neighbours as extras and the graffiti artists as commons producers capitalised through the fact of not separating art and life in a public space. Through parody, by bringing out the stereotype to the excess and by offering ourselves as inverted image, we wanted to neutralise the performative strength of that which the visit, with its press ad, was to inaugurate.

So parody was to make the naturalised violence visible by reflecting it in a comic counterperformance, but also to avoid that visitors would feel threatened by our presence, thus making it difficult for the press to criminalise us or portray us as radicals affected by an irrational phobia towards tourism. Some of us dressed up with accessories evoking the National Geographic reports and went to the event with a “safari look". The European colonial imaginary of Africa was the place of the parodic excess we found to mirror the capitalist coloniality within the metropolis.

We should clarify that we were surprised by the sociological composition of the group. We were expecting a group of foreign tourists, but it was rather formed by local people from other wealthier neighbourhoods of Málaga, half young and half old. This seeming paradox gets solved once we dissociate the image of the tourist from the one of the Global Northern foreigner, since in a city like Málaga we are all increasingly becoming tourists. The more the touristic dispositive shapes spaces and relations, the more any one becomes its best immediate product: the tourist (and/or its other face: the precarious worker).

The “plan” emerged on the fly: we waited for the visitor group at the plot ‘Victoria, ¿de quién?’, pointing at them with cameras, mobile phones, binoculars, etc., while some of us filmed and took pictures of the scene from outside. Meanwhile, one of our Barrial Geographic “expert guides” gave a lesson in an embellished academic tone about cultural appropriation, capitalist opportunism, and tourist groups in impoverished neighbourhoods. The game was to convert their consuming practice into the object of our sights, insights, and recordings, the same way we felt our art-life practices were being converted by their consuming practice. Where one group was privatising the collective wealth in the name of the neoliberal freedom, taken as public space commodification, the other group was defending it, giving a political twist to those notions of freedom and public in the name of the commons.

As we say, our ultimate goal was not to avoid the visit itself but to invert and transform it into filming supply for a Lagunews episode. If we were working for the profit of a private business, the guided group and the business itself would work as extras for Lagunews.

What happened? The politics of the event

Our internal rule was to not engage into any dialogic confrontation, neither with the guide nor with the assistants, in order to avoid a personalisation of the conflict, but also because we were performing the subject-object game, typical of scientist-capitalist-patriarchal relations: the same one that the cultural industry and expert knowledge were establishing with us. The subject-object relation is based on the neutralisation of the other’s subjectivity, it places a hierarchy in a binary relation only sustainable over time by imposition and colonization: it is a power-knowledge monologue. Whether our parodic inversion was to be understood, The idea was that if our parodic inversion was understood, this element of violence, which we were also applying at our own scale by converting the tourist group into an object, could help draw a connection to the violence experienced by the neighbourhood when it is visited in that way, and by extrapolation, to further forces of gentrification forces, too. Humour could allow us to introduce a difference to assert our gesture as an act of defensive violence. In any case, the conflict had been raised. So the tourist group reacted and singularised, too.

Our intention of acting without interacting with the tourist group fell apart when the old people started to call us and justify their visit. An older woman came to complain to us that she had come to visit the house where her mother was born and there was a horrible graffiti on there. Another gentleman protested that thanks to the art historian now he could appreciate the graffiti as “art”, and until that point he had that it was urban dirt. In another moment, somebody said that if not for the tourist guide group she would not have come to Lagunillas since it is a scary place… And then both groups’ scripts and performances broke down, the groups mixed, the object-groups, bound to the other’s observation and enunciations, became dialogical subject-groups, giving rise to discussions and conversations where we tried to explain the reasons of our action so much as invite them to visit and support the neighbourhood with the neighbours and not without them.

At this point, the fear and displeasure of the old people contrasted with the reaction of the young people. Some of them came to apologise, to express their sympathy for the neighbourhood and to explain that they didn’t know that the business had refused to speak with us. They listened to our stories on the effects of cultural tourism in Lagunillas (displacement, rent increases, the threat to singularity, the danger of pending eviction, etc.). Some of them abandoned the tourist group and stayed with the neighbours group. We exchanged contacts. And we finally had beer together in a bar in the neighbourhood where, once the visit finished, the tourist guide also came and friendly debate with us from our different positions.

Lagunillas is a neighbourhood that points to the future in its declarations (The association ‘Lagunillas Por Venir’ [a word-play containing two senses: ‘Lagunillas To Come’ and ‘Future Lagunillas’], an establishment and a Facebook page called ‘Lagunillas: El Futuro está muy Grease [a phonetic pun between gris (grey) and the famous musical Grease, affirming a concern about the future by using an absurd and funny association]), which is nourished by gestures of the mutual city, of creativity and collective intelligence, which dwells with a nonconformist smile in the heart of touristic capitalism. Will its smile be contagious? Whose Victor(y)ia?

Link to the action video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1J8htkeH3m8&feature=youtu.be

[1] The plot of land is in the place where the birth house of the historical republican feminist Victoria Kent used to stand. It was an old abandoned house that had previously been requested by a cultural collective. The name of the plot calls to local authorities by asking a question via a play on words between Victoria Kent and ‘victory of whom?’

[2] Lagunillas self defence: neighbourhood struggles and gentrification. Description and program http://www.malagaldia.es/2017/03/17/lagunillas-se-defiende-luchas-vecinales-y-gentrificacion/

[3] Lagunews on the occupation of the plot ‘Victoria, ¿de quién?’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i2nxReJ2Tes

[4] Merdellón is a derogatory term used in Málaga to refer to “low” neighbourhood people and their cultural practices. Although etymological the word seems to come from the Latin merda and it already appears in ancient Italian to refer to «male and female servants that serve with lack of hygiene», the urban legend says that comes from the French merde de gens (“shitty people”, despite in French it would be gens de merde). According to popular legend, merde de gens was how the French soldiers referred to the local population during the two years of Napoleonic occupation (1810-1812). This explanation of the word, non-defendable as etymological truth, is a mythical truth of the popular knowledge by its performative repetition in the self-referential tales of the city. The merdellón relates to the local ghost of the violent occupation of the territory by a foreign or exogenous group, the ghost of an undermined local culture in the cultural hierarchy of Europe, the ghost of the self-deprecating and the interclass contempt that befalls over a social group because of a “non-suitable” image for the tourist visitor nowadays. Merdellón relates to a ghost that tours the presences of the neighbourhood at declassing, but the neighbourhood transforms it into a site for enunciation in response to the classist pressure of the institutional branding of the touristic and cultural Málaga, what explains the interpretative and sensitive frame of Lagunews’ videos.

[5] See Gerald Raunig’s text in this issue: http://transversal.at/transversal/0318/raunig/en.

[6] “Berlin graffiti artists destroy their art to fight gentrification” http://skrufff.com/2014/12/berlin-graffiti-artists-destroy-their-art-to-fight-gentrification/

[7] Despite both politicised graffiti and activism being able to breathe energy into gentrification in the neighbourhood, the neoconservative government policy of Málaga is quite biased and repressive in regard to the visibility of statements in public space. In April 2017, the Málaga council threatened a Moroccan association with a 600€ fine if they did not erase a mural from the door wall. The mural represented a young Moroccan boy looking towards Europe from behind the border fence and a black African woman sustaining a balance on her shoulders saying ‘There’s no justice without equality’ http://cadenaser.com/emisora/2017/04/18/ser_malaga/1492532927_225371.html. However, three years before, Obey had made a huge mural at the request of the local government. The original message used to say ‘Peace and Justice’, but obeying the sponsors’ demand, Obey changed it for ‘Peace and Liberty’, a much more confortable message for the neoconservatives.

[8] Oracio Espinosa, “Turismofobia: patologizar el malestar” http://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/opinions/Turismofobia-Patologizar-malestar-social_6_660443975.html