10 2017

How to Speak Precarious Histories from a Precarious Position?

From Guests to GUESTures

“Even though multiple generations of migrants lived through every major event in the history of West Germany, from the Grand Coalition and the 1968 student protests to the kidnappings by the Red Army Faction and the fall of the Berlin Wall…with a few key exceptions, what is immediately striking about the historiography of the postwar period is the curious absence of guest workers.”

Rita Chin, The Guest Worker Question in Postwar Germany, 2007.

“Among the migrant workers in Europe there are probably two million women. Some work in factories; many work in domestic service. To write of their experience adequately would require a book in itself. We hope this will be done. Ours is limited to the experience of the male migrant worker.”

John Berger and Jean Mohr, A Seventh Man, 1975.

The following text examines, reflects, and shares processes of research and production I conducted during the development of GUESTures, a long-term art project on and with "guest worker" women who came from Yugoslavia to work in large electronics factories in West Berlin in the late 1960s.

PART 1 [RE-SEARCH]

—

My grandparents – grandmother, Marija, is in the middle, arms crossed, grandfather, Vinko, to her left – are seen roasting a pig in a muddy field. Behind them, a tall tower pierces the image, making it look as if two photographs are superimposed on top of one another, like two worlds that are sewn together but we cannot see the seams.

My grandfather arrived in 1969 to work as a metal worker at the Georg Grube automobile factory in a small village called Willroth in an area of West Germany called Westerwald. He was soon followed by my grandmother, who initially worked as a childminder, then in a soup factory, and finally as a waitress at a local Gasthaus catering to the truck drivers who would take breaks on the motorway that passed the village.

Four years before my grandfather arrived to Westerwald, the entire local mining industry was shut down after 400 years of continuous mining in the area. The car factory where he worked was built on the same land as the closed mine during the boom of West Germany’s "economic miracle" (Wirtschaftswunder). A local notice board informed us that it was the last operating mine in the region and “was closed due to the depression in the 1960s.”

——

I arrived in Berlin at the tail end of winter in 2009, with the whole city covered in snow. I landed at Schönefeld Airport, and as soon as I left the plane the sharpness of the air enveloped me and I couldn’t shake it off until the end of the two-month stay as an artist-in-residence. My studio was in a street that would have been sliced by the Wall 20 years ago. Now, there is a long temporary board at the end of the street that announces a more permanent memorial for the Berlin Wall. Next to it is a makeshift show home, advertising new flats being built in the "Neue Bauhaus" style. It felt appropriate to start my (re)search in a city that constructs its memory with the same intensity as its many construction sites are building stylish new flats.

I arranged to meet the historian Dr. Monika Mattes in Kreuzberg. She told me that in the late 1960s the majority of workers in large electronic and telecommunication factories in West Berlin were women – for example, in the Siemens factory, 67% of workers were female guest workers. I am surprised to hear this as it clashes with the masculinist image of a worker, in particular in the electronics and telecommunications industry, but especially with the image of a male migrant worker that still dominates the official narratives and collective imaginary of the era. I later read the text Monika co-authored with Esra Erdem in which they describe how the arrival of female guest workers from outside Germany was precipitated by the specific gender policies of the German government at the time. German policies did not consider it desirable to make up for the gap in the labor force by mobilizing non-working housewives and mothers for full-time jobs in the low-wage industrial sectors. This view was coupled with a belief that working outside the home would threaten women’s ability to have and care for children. At the same time, it was difficult to fill vacancies in the textile, clothing, food, electronic, and hospitality industries posted through the employment service with unemployed German women.

“The advantages of migrant women over German women were their young age, the health-based selection and the fact that they were willing to work full time. Most were assigned to work shifts, to do piecework and to work on assembly lines … in jobs that took a toll on their health, and which German women refused to work at [sic]” (Erdem and Mattes 2003:168).

The politics of the time were also embedded in the language: labor migrants were called "Gastarbeiter" in German, meaning "guest worker," linguistically framing the temporary nature of their status in Germany, whilst also avoiding the connotations of "Fremdarbeiter" (alien worker), which Nazis used for forced labor (Chin 2007:52). The officials in Yugoslavia termed it "radnik na privremenom radu u inozemstvu/inostranstvu" (worker who is temporarily working abroad), also stressing the temporary character of the emigration (Novinšćak 2008:131). However, the German word Gastarbeiter never really got translated into colloquial language, instead it remained and became Gastarbajter.

———

I visited the Landesarchiv Berlin next in search of photographs (proofs), whereupon I am faced with photographs showing rows of women, some in the white lab-like coats, working in factories, faces down, focused on their task. I am reminded of Brecht’s words: “The situation has become so complicated because the simple 'reproduction of reality' says less than ever about that reality. A photograph of the Krupp works or AEG reveals almost nothing about these institutions. Reality as such has slipped into the domain of the functional. The reification of human relations, the factory, for example, no longer reveals those relations. Therefore something has actually to be constructed, something artificial, something set up” (Benjamin, 1931:24).

In the right hand corner of one of the photographs’ archival cards, the following is written:

Verweisungen / Bemerkungen: 10 Arb Ausländische Arbeitnehmer. Fotograf: I. Lommatzsch. Date: 5.10.1974.

What is it that I am looking for, in any case?

————

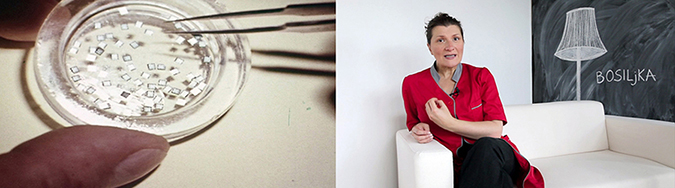

Soon afterwards, I met Bosiljka Schedlich, founder and director of the Southeast European Cultural Center in Berlin (in 1991), who, in 1987, put together the first ever exhibition of photographs and testimonies of guest worker women, entitled Der Weg: Jugoslawishe Frauen in Berlin (The Journey: Yugoslav Women in Berlin). The exhibition took place in Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin to coincide with the 750-year anniversary of Berlin, and subsequently toured across Germany and Yugoslavia. Until recently, the exhibition panels were stored in the vaults of the museums of Yugoslavia in Belgrade, and I haven’t had a chance to see them until this year (2017), when both Bosiljka and I took part in an exhibition curated by WHW at Galerija Nova, Zagreb.

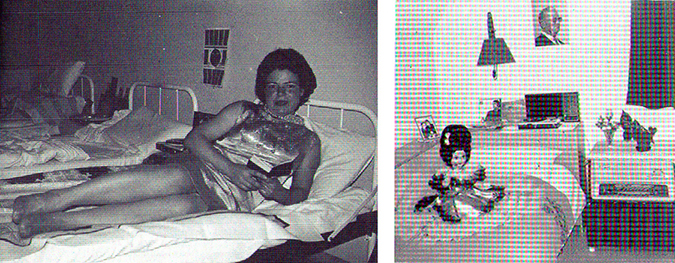

The two photographs above are from Bosiljka’s exhibition catalogue, which she told me were taken in the workers’ dorm in Flotten Strasse, where Bosiljka arrived as a guest worker to Berlin in 1968: “The beds we slept in were hospital beds. When the factory production (towards the end of the Second World War) stopped, this became a hospital. We kept seeing little, old people with wispy white hair in the basement, who were afraid of us, and locked their doors when they saw us. They were German refugees who fled the Russians, and our language probably sounded similar to them.” Bosiljka speaks in a clear voice. Her words paint vivid images in my mind. She continues: “I came by train to Zagreb and I don’t remember that journey. They put us up in a hotel in Zagreb. The next day we flew out and I remember that in the airplane I suddenly looked out of the window and saw cirrus clouds... white, they were so beautiful, like snowflakes and I thought 'God how I wish to lay down onto that cotton. Nothing would ever hurt me.' I had the feeling that I had no skin on me. Saying good bye was so hard.”

—————

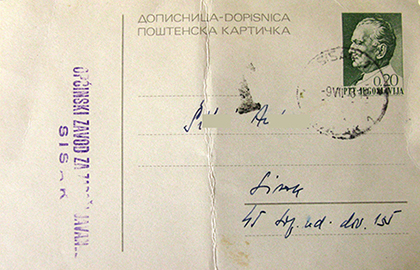

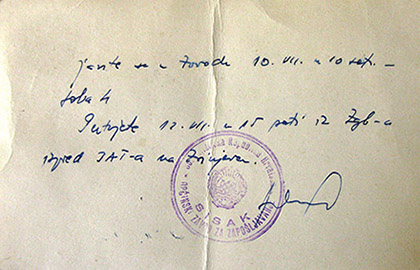

Notification from the employment bureau. Courtesy of Ana S. and the artist.

That week I got a phone call from Ana. She heard about my project from the announcement the priest made in her local church (I had to become creative with my research). We met in her flat and Ana told me about her upbringing, her life in Berlin, and showed me her letters.

SISAK 18 July, 1968 Dear Ana, We’ve received your long awaited and longed for letter in which you tell us that you have arrived safely to Germany. We’re all well. In your letter you say that it’s cold over there, so when you receive money, buy a coat or a two-piece suit, but not a spongy one. Ana, you left on Friday and Viktor followed right after you on Saturday. Ana, you know very well how sorry we are that you’re gone but what can we do when it’s got to be this way. Mileva always talks about you and asks when you’ll send a transistor radio and a baby doll, and we always lie to her and tell her that you’ll come for New Year. Ana, pay attention to what your uncle is writing and be a good and respectable girl as you were here with us, because now that you are in a foreign country you should also be good, as that’ll be respected by any decent man. Ana, you can always come back to stay with us and our door is always open to you as it is you who has raised Mileva. I’m writing to you as if you were my child and my eyes are now filling up with tears. Ana, look after yourself now and learn the language, I think that you will adjust well because you are good. Ask about what you don’t know, because the old proverb says ‘the one who asks does not lose her way,’ and now receive lots of warm regards from your uncle and Mileva and all others who were asking about you. We are sending you a picture of Your Mileva. (Child’s handwriting) Ana, buy a baby and a transistor. Love, Mileva.1

——————

Inside the guest workers’ dorm. Color photograph. Courtesy of Gordana U. and the artist.

Soon afterwards, I met Jana, Gordana, Marija, Vinka, Jela, Smilja, and Zlata. There are many common threads that tie their stories together, regarding the manner in which their migration was bureaucratically organized: They applied for work with their local employment bureaus who worked together with the German Federal Office for Labor Recruitment and Unemployment Insurance, who in turn worked together with the companies that placed a request for workers. Each person had to undergo a medical examination. The candidates that passed medical examinations were offered work, whereas the others were turned down. The jobs offered to successful candidates could be based in any part of Germany. The contracts were usually for twelve months during which time the labor recruits “could not change positions or leave an unpleasant employment situation without the risk of losing their work permit” (Chin 2007:39). German companies also paid for the workers’ travels to Germany under the conditions that an early termination of their contract meant that employees were liable to cover the costs of their travel incurred by the company. In some cases, this meant that guest workers had to remain in jobs they were not necessarily happy with or in conditions of pay and accommodation that were not of an agreeable standard.

Several of the women I interviewed said that they did not have much money when they began their employment, because they were not paid well, and that made the possibility of changing jobs or going back home increasingly difficult as they could not afford to pay back the travel fares. Upon arriving in Germany, the guest workers were mostly accommodated in dorms provided by their employers, who deducted the costs from the workers' salaries. They shared rooms with up to seven other women sometimes, most of whom they met for the first time during their shared journeys to Berlin. Most were in their early 20s. Others like Gordana were not yet 18. Gordana recounted the difficulties she experienced when she started out in Germany, as it was her first time away from home. Other women shared their experiences of disorientation and insecurity about their new lives, finding solace in the knowledge that their stay was only temporary and that they would soon be returning home.

Excerpt from The Origin and Structure of the Yugoslav Worker in the Federal Republic of Germany, by Ivo Baučić, Zagreb, 1970.

PART 2 [RE-ENACTMENT]

Inside the Telefunken factory, ca. 1970. West Berlin. Color photograph.

Courtesy of Gordana U. and the artist.

“I worked at Telefunken for thirteen years. Then we got sacked. Maybe we would not have been sacked, but in 1981, when Tito died, we all walked out of the factory together, because there was a live relay of his funeral in Belgrade. We knew about it that day, because they came from the Yugoslav consulate to the front of the factory and told us that it would be nice if we could go and watch the funeral on television, but our company Telefunken wouldn’t allow it, because we were working. There was always a German person on the conveyer belt with us. Now I work on my own, but before I always had somebody next to me on the conveyer belt. That’s why they wouldn’t let us go. But we went anyway. Some went and some didn’t have the courage to leave. I left... not only me, many of us went, but the next day we came to work, and they wouldn’t let us go straight to our work stations. Instead they called us in to see the boss.”

Excerpt from an interview with Gordana, reenacted in the video GUESTures.

Please note that Tito died in 1980. The above text is a translation of Gordana's exact words in Croatian.

——

In 2010, I took part in two exhibitions where I had the chance to test out different forms and strategies of display, which shaped how I further developed my work: the exhibition “Over the Counter: The Phenomena of Post-socialist Economy in Contemporary Art,” curated by Eszter Lázár and Zsolt Petrányi for Kunsthalle Budapest, and the exhibition Izloženost/Exposures in Banja Luka (my hometown) curated by Antonia Majača and Ivana Bago, at the invitation of Protok, a local art organization. The latter exhibition poignantly and somewhat uncomfortably was located in the premises of a disused part of the Čajavec television factory (my late uncle used to work there), which was facing closure itself. For both exhibitions, I displayed a selection of testimonies and personal letters as well as immigration documents from the guest worker women I had met alongside a collection of photographs from their albums. I presented the material in a form that echoed strategies of archiving such as using filing folders, acitate transparencies, and 35mm slides, which needed to be placed on the overhead projector or inside a handheld slide holder in order to view them. The installation display asked the exhibition guests to do some work in order to access the content, de-centering an impetus for a coherent and linear narrative and foregrounding personal storytelling as a valid form of history from below. By presenting fragments of research this way, my intention was to not reproduce the institutionalizing impulse of an archive as an "authoritative and monolithic power, with its homogenising instrumental desires" (Edwards 2001:10) but instead offer a gesture towards a counter-archive; towards a fracture and fragility of the frame – of photograph/image, but also larger institutional frames, including those of the nation-state.

Collective reading workshop, exhibition "Izloženosti/Exposures" ex-factory Čajavec,

Banja Luka, Bosnia-Herzegovina, 2010. Photograph: Marcus Kern.

These "work stations" were also a focal point in creating spaces for collective readings of the archive, in which the visitors as well as local migrant groups were invited to engage with the material and also to contribute their own stories. This way the "archive" is always moving, always in a state of change and migration. During the Izloženost/Exposures exhibition, the first collective reading took place, with each person taking turns in picking up a transparency and reading guest workers' testimonies aloud to the others – a deep sense of intimacy was felt in the room, while we each took turns in giving our voices to the words on the page, re-enacting another person’s words, becoming them for a moment, embodying their journey. One of the guest worker women, Zora, whom I met earlier that year in Berlin, happened to be visiting Banja Luka, so I invited her to join us. Those present asked Zora questions about her experiences of migration, and what started as a mediation of the guest worker stories through the material held in the archive, soon became a more direct mediation of a personal lived memory in that present moment. Collective reading workshops became an intrinsic part of the GUESTures project – in its latest iteration during the exhibition at Kullukcu Galerie in Munich in 2013 (in collaboration with Katja Kobolt and Natalie Bayer) – it expanded to include local migrant groups who would contribute their stories to the “archive.” However, during that first event I began to sense that the project was not finished and that I wanted to create a space for further experimentation with the questions and notions of historical truth and authority; voice and testimony in its relationship to fiction and documentary.

GUESTures exhibition, installation view, SC Gallery, Zagreb, 2011.

Back in London, I joined a group called Implicated Theatre, where we learn, devise, and use Theatre of the Oppressed techniques and methods developed by Augusto Boal, Brazilian radical theater director.2 I also became interested in the method of "reenactment," which is often used in live reconstructions of historic events, often of a military nature by amateur enthusiasts. Contrary to the grandness of these large events, I was drawn to the intimate, mimetic potential of reenactment as used in verbatim theater, often to re-stage marginalized stories or public enquiries such as in the plays I saw at the time, Tactical Questioning: Scenes from the Baha Mousa Inquiry by Nicholas Kent and London Road by Alecky Blythe. Clio Barnard’s film The Arbor was highly influential. It used actors to lip sync the voices of real people. Each of these works questioned documentary's aspiration to collapse the distance between reality and representation while simultaneously not losing the political urgency or veracity of the document. The verbatim method offered a way of working with the material, whereby its inconsistencies, its "truth" is not ironed out and the messiness of remembering is not erased, while Theatre of the Oppressed opened up political questions of where power is located and how to subvert it.

Still from GUESTures | GOSTIkulacije, double-channel HD video with archival footage, 33 minutes, 2011.

The video GUESTures (or GOSTIkulacije) is a double-screen video, although it doesn’t start its life as such. It starts with a reenactment of edited transcripts of interviews I conducted with Bosiljka, Jana, and Gordana; or rather it starts with me meeting actress Adna Sablych and giving her the sound recordings. Like me, Adna comes from Bosnia-Herzegovina, and like me, she also arrived in 1992, fleeing the war. Our own histories as migrants, as women, as artists, are present in the video, sometimes in an obvious way – for example, in the conversation with Jana, I speak of my own migration to the UK – but more so in subtle ways. It is there in the way Adna inhabits gestus in a Brechtian sense, the way she "embodies the attitude" of the characters or in the silences which punctuate her speech. Our histories and stories merge and although there are certain historical specificities to the stories the guest worker women recount, I see GUESTures as a video (and a performance) that is about the present. It is about recalling the nowness of the crises not of migration, but of empathy and of political structures that can deny human dignity on a daily basis to such a degree as to produce the so-called "migrant crises."

GUESTures is, after all, a made up word – bastardized, occupied, holding a stranger, a guest in its midst, and holding a gesture towards a possibility of a counter-archive, counter-histories, and counter/new languages.

References:

Chin, Rita. (2007). The Guest Worker Question in Postwar Germany. Cambridge University Press.

Baučić, Ivo. (1970). "The Origin and Structure of the Yugoslav Worker in the Federal Republic of Germany" (Porijeklo i Struktura radnika iz Jugoslavije u SR Njemackoj). Institut za Geografiju Sveucilista u Zagrebu (Institute for Geography, Zagreb University), Vol. 9. Zagreb.

Benjamin, Walter. (1931). A Short History of Photography. Oxford University Press.

Berger, John and Mohr, Jean. (1975). A Seventh Man: A book of Images and Words About the Experience of Migrant Workers in Europe. Penguin Books Ltd.

Bezirksmuseum Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg. (2009). Conference material from the symposium: "Introduction to the Guest Workers in Germany: The Ups and Downs of Contradictory and Unmade Decisions," personal hand-out, translation: Dorte Huneke, Bezirksmuseum Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, Berlin.

Erdem, Esra and Mattes, Monika. (2003). "Gendered Policies – Gendered Patterns: Female Labour Migration from Turkey to Germany from the 1960s to the 1990s." In: European Encounters: Migrants, Migration and European Societies Since 1945. (Eds.) Ohliger, Rainer; Schonwalder, Karen; Triadafilopoulos, Triadafilos. Ashgate, pp.165–185.

Edwards, Elisabeth. (2001). Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Oxford and New York: Berg.

Novinšćak, Karolina. (2008). "From ‘Yugoslav Gastarbeiter’ to ‘Diaspora-Croats’: Policies and Attitudes Toward Emigration in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Republic of Croatia." In: Postwar Mediterranean Migration to Western Europe. (Eds.) Caruso, Clelia; Pleinen, Jenny; Raphael, Lutz; Lang, Peter, pp. 125–143.

See also:

Kuburović, Branislava. (2011). “GUESTures: Awakening the Space of Precarious Knowledge” In: http://guestworkerberlin.blogspot.co.uk/2011/11/guestures-awakening-space-of-precarious.html (also “Margareta Kern’s GUESTures” in "Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory," Volume 23, 2013, Issue 2).

Shonick, Kaja. (2009). “Politics, Culture, and Economics: Reassessing the West German Guest Worker Agreement with Yugoslavia.” In: Journal of Contemporary History, Volume 44 (4), pp. 719–736.

---

1 Translated from Croatian by Margareta Kern.

2 Boal proposed the term "spect-actor," dissolving and reconstituting boundaries and roles between the spectator and the actor, whereby audience(s) becomes an active and an implicated participant in the play.