03 2025

Two Sweet Illusions and One Bitter Truth of the Student Protests in Serbia

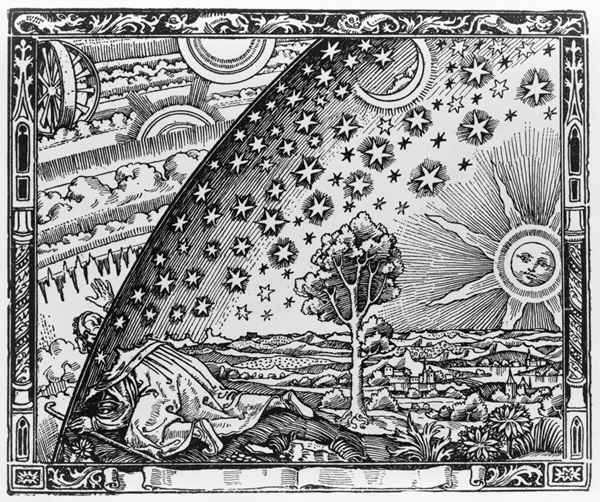

Flammarion woodcut; author: Nicolas Camille Flammarion

Flammarion woodcut; author: Nicolas Camille Flammarion

The famous Flammarion woodcut, an iconic depiction of the world on the threshold of the Renaissance, illustrates a surreal scene: having reached the end of the world – the place where the firmament touches the flat earth – a young man, probably a pilgrim, stuck his head through the membrane of the sky and stared at … we do not know what. Numerous interpreters of the symbolic meaning of this illustration, most likely created in the 19th century, have not found any conclusive explanation for what this figure saw beyond the known world. Some saw the caught sight of God in the vague contours, others recognized the devices of a cosmic mechanism, and others still, a pictorial representation of Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover. What is obvious and indisputable in this illustration, however, is its true and only theme, the moment of revealing the unseen, or rather the exhilaration that accompanies this act and that we, the observers of this scene, share with its protagonist, the figure of a person who dared to pierce the horizon of the existing with his head. Everything else is secondary – the kitsch of trivial reality.

In its symbolic meaning, this old woodcut by Flammarion tells us more about the student protests in Serbia than all of today's media combined, whether social or anti-social. Horny for the spectacle, like adolescents on Porn Hub clips, they saturate our eyes with one and the same image, repeated in an infinite loop: a mass penetrating public space, a mass accumulating and rising, swollen to bursting, a mass in action, a mass from above, a mass from below, a mass on the left and on the right, in motion and at a standstill, in detail and close-up, cynically diminished in the pro-regime perspective, optimistically enlarged in the anti-regime one. And then, again the mass, and then even more masses… No matter how spectacular, all this visual overkill, willy-nilly, serves one purpose – to fan two sweet illusions and conceal one bitter truth.

The first illusion is that the mass, a hundred years after its first entry into the political arena of the modern world, is still a relevant political subject, for better or for worse. In the bourgeois-liberal brains, clogged by ideological limescale, it still plays an important role, although it no longer appears on stage without a costume – once, in the dirty, smelly rags of populism, and on another occasion, in the fashionable outfit of civil society. While the audience curses and spits at the first, it enthusiastically applauds the latter. That is why the European, and, generally, Western public hardly takes notice of the Serbian student protests, regardless of their massiveness. The mass without costumes, no matter how spectacular its media presentation, remains invisible. Of course, everything would have been different if the students had taken to the streets under the joint flags of Serbia and Russia, called for reunification with Kosovo and chanted for Putin. Horrified by the savagery of a primitive Balkan tribe, misled by populist manipulations, Europe would find one more reason why Serbia has no place and can have no place in its "circle of civilization." If, on the contrary, they raised the flags of the European Union, NATO, or those of rainbow colors and announced that they took to the streets in the name of democracy and European values, and against illiberal autocrats, such as Putin, Orban and Vučić, the whole of Europe, led by Ursula von der Leyen, would stand on the side of the brave civil society that leads Serbia into the European future. But alas, the Serbian students haven’t done either. Moreover, they, along with all those who publicly stood by them, are not a mass at all, something that even the media sympathetic to them cannot understand, nor portray.

Therefore, the idea that masses in the streets today are still able to radically change the given reality is a pure illusion, surely a sweet one, but still a mere illusion. If not before, this became clear on that Saturday long-ago, February 15, 2003, when millions of people in six hundred cities around the world took to the streets to protest the announced invasion of Iraq, the illegal military intervention and occupation of a sovereign country, which its perpetrators legitimized before the Security Council and the entire world public with cheap, ridiculous lies. People reacted with the largest mass protest in the history of mankind. On the streets of Rome alone, the crowd numbered three million. London experienced the largest political rally in its history. And what happened? Nothing! The "coalition of the willing" did its job, sent over 150,000 people to their deaths, two-thirds of whom were civilians, and drove millions of Iraqis into exile. Liberal Western democracies, otherwise so proud of their democratic values, completely ignored the will of the masses. They broke the laws, committed crimes, and all of this not only without punishment, but also without any political consequences. Today, as a new "coalition of the willing" for arming and for war is being created in Europe, demonstrations are still taking place, only in Serbia. Against what, or for what, Europe does not know, nor does it care.

There is, however, another, equally sweet illusion – but an illusion nevertheless – that the students and all those who joined them, in fact, represent the people and that the entire protest is essentially about the conflict between a good people and a bad state. So, on one side is an honest, uncorrupted, truth-and-justice-seeking people, that, led by students, took to the streets to fix the rogue, dysfunctional institutions of their "failed" state. On the other side, of course, is the corrupt and alienated political elite that has hijacked and ruined the state. In this sense, the ultimate purpose of the protest is clear and unquestionable: to cleanse the state of corrupt elements and thus perform a kind of general overhaul on it, after which it will function as new. Serbia will eventually become a normal, orderly state in which institutions do their job, laws will be respected, and a free and independent public, together with an ever-vigilant civil society, will remove possible deviations as it goes along. This way, capitalism will finally get its optimal legal and political framework within which it will initiate continuous growth, without crises and conflicts, raising, like a tidal wave, the standard of living and general well-being of all members of Serbian society. The long Serbian nightmare of an "unfinished state" will finally come to an end. The Serbian people will wake up to the reality of their restored state, which, like a Swiss clock, will steadily tick the time of happiness and well-being, if not until eternity, then at least until death do them part, which, of course, will never happen.

And what about political parties, that is, opposition politicians, is there no place for them in this story about a happy Serbian future? It is true, they are not among the main actors of the Serbian student protests, which does not mean that they are not present. Like hungry crows, they perched on the surrounding observation posts and now wait for the regime to collapse under the pressure of the masses, lay on its back and reveal its belly, so that they could crawl into its bowels and start feasting. If not, so be it. They didn't risk anything, so they won't lose anything. And when it comes to waiting, they know best how to do it … even forever if needed. In fact, the entire political sphere, i.e. the party and parliamentary system, supposedly the very backbone of modern democratic society, is almost completely absent from the event itself. Maybe because it has become irrelevant. To avoid any confusion – it seems that political parties and the parliamentary system itself have become redundant in the political life of (Serbian) society. Moreover, we do not miss them at all. On the contrary, the true experience of freedom, hope, human dignity appeared only when we pushed them aside.

This leads us to the question of the bitter truth hidden behind the sweet illusions. Nothing reveals it better than the fundamental paradox of the Serbian student protests – the obvious disproportion between the tremendous energy generated by the protest, the mass mobilization of the broadest strata of citizens, their spontaneous collective creativity, socially formative self-organization and self-discipline, superior public self-articulation, their persistence and perseverance, all of which are unprecedented, not only in Serbian, but also in modern European history – and, on the other hand, the extreme minimalism of their political demands. All they are asking for is that the existing law be respected and that it be done publicly. Only that and nothing more. But, we see, that is too much. They are unrealistic, because they demand the possible.

The students, and all who followed them, did what they dared not do – they took liberal democracy at its word, for which it will not forgive them. Cynicism was and remains her intrinsic modus operandi, the tacit assumption of any faith in its ideals: in the people as the sovereign in its democratic nation-state and international order, based on rules and laws; in the figure of the free individual as the center of the entire universe who, in equality with others, through their democratically elected representatives, regulates the life of the community for the benefit of all; in an institution of the public, independent and objective, which in the free exchange of different ideas easily produces rationality and equity; in the rule of law, a strong and active civil society, and, finally, in the untouchable private property and the free market based on it, whose invisible hand will sooner or later feed all mouths and ensure a solid roof over everyone's head...

But, have we forgotten that, even before that roof collapsed on its head, Serbia blindly believed in this ideological kitsch twice already? First, it was 1990 when, together with the masses of Eastern Europe, it took an epochal historical turn known as the fall of communism. What followed was the reality of nationalist hatred, criminal privatization, wars, ethnic cleansing, crimes, territorial mutilation, moral humiliation, economic decline. About ten years later, in the so-called October 5th Revolution, Serbia once again rushed headlong into the liberal-democratic future, only to immediately end up in an endless transitional dystopia, on the scabby periphery of European and global capitalism, in a constitutional-territorial makeshift, under the corrupt elites and institutions, in a state of permanent incompleteness and an endless waiting for a miracle – democracy as it should be, or rather as it allegedly already exists, but somewhere else, in Europe, in the West...

Does anyone today, after this, really seriously think that Serbia is trying to repeat it again, that all that emancipatory energy, the will for radical change, unprecedented unity and solidarity, was set in motion by a handful of incompetent losers, who are now trying to pass the exam in democracy for the third time?

Flammarion's woodcutter did not place his main character in the center of the world, an idyllic landscape of the earth as a flat plate, clearly limited by the horizon of the known and the possible. On the contrary, he dragged him to the very edge of that world, where the firmament pressed him to the ground, forced him to bend, kneel and at that very place break through with his head to the other side, into the world beyond the horizon. He sees this world. We, who stand in the center, do not. Like in Serbia today – we see the mass, but we do not see what it sees, because its head is already beyond the horizon. The contours are vague and impossible to name. But anyone who hopes that a well-known recipe awaits us on the other side is sorely mistaken: a change of government; new elections; an assembly composed of authentic representatives of the people; an uncorrupted, efficient executive that implements laws without reservation; a new indigenous civil society, truly independent media, and similar flat-earth fantasies of a disintegrating liberal democratic order. After all, this very act of rebellion and protest, in its enormous energy and dimensions, is motivated, above all, by the existential experience of the end of an era, of a world whose truths and lofty ideals have been exposed as lies and empty illusions. Nothing would have happened if a botched canopy had fallen onto a few unfortunate people in Novi Sad. But it did not, rather the entire firmament of the ruling ideology collapsed onto society, or more precisely, onto what remained of it after decades of its neoliberal dissolution. And what has risen to revolt today is the remnants of that society, expelled from state institutions, ruined by legal paragraphs, disgusted by ideology, ridiculed and spat upon in mass culture, silenced in parliament and sold out, for nothing, on the labor market. That is why what we see in the streets of Serbian cities is not a mass, but a society. Only the media, as they are, have neither the words nor the images to tell and show this. People have taken to the streets because it is the only place where they can still realistically articulate solidarity as a formative experience of society. Because that society, which has itself been left without a roof over its head, is the only roof that can protect them from the firmament that threatens to crush them. The world, as it is today, is no longer a place to live, but a threat to the very survival of life.

That is why it is precisely the students who led the revolt. Not because they, as some avant-garde, know the way to a better future, but because they have no future. The nation to which they still naively and innocently belong today, by the end of the century, will just be a bunch of helpless old people, far more numerous than the children who could support them; the language that they speak and learn is already digitally dead today; the technology that still fascinates them, rapidly forges slave shackles and weaves nooses around their necks; if they are not fried by nuclear warheads, they will be fried by the infernal sun. They have no choice. Either they will radically change the world we threw them into, or they won't exist.

Language editing: Lina Dokuzović