10 2010

Something Other Than Administrated “Quality.” Art Education and Protest 2009/1979

Translated by Erika Doucette

Digital Locks

Returning from the summer break at the beginning of October 2010, a few noticeable changes had taken place in the main building of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. In the past months, the graphic design on the signs throughout the building had been revamped, a new exhibition space had opened, the old painting gallery had been reopened to the public after having been closed for an extended period of time and in a very specific place, like techno-social signs heralding the new old order there were now locks with electronically generated numeric codes. These security tools were installed on the large, glass-paned wooden doors that form the entrance to the main hall (Aula) that, since 2009, had been the place of occupation, public plenaries and debates, working groups, people’s kitchens, parties, concerts and art actions. Evidently, the access to the Aula was to be more strictly regulated in the future. The fact that such a measure was taken is fully understandable from the point of view of the Academy’s administration and the state real estate company that owns this classicist style art palace built during the late Habsburg era. The turmoil of the protests and strikes had manifested itself in an especially visible manner within this space. The long semester break had come just in time to restore some order.

However, the digital locks (which may have been installed a long time ago, but were only now able to unfold their full semiotic effect) are indeed an extremely weak symbol. They seem to helplessly want to proverbially bar entry to a development that those responsible for installing the locks are hardly capable of controlling. The debates on the dedemocratization, economization and the transformation of universities into edu-factories have been going on for several years now and become even more intense since October 2009 when the university occupations in Austria and other countries began. Within the Academy of Fine Arts and its extended contexts the debates and actions connected to and inspired by these issues have brought about a number of tangible changes. Analyzing the existing hierarchies and working conditions within the higher education system and, at times interventions within them, have sharpened the actors’ awareness of the glaring social and economic fault lines within and beyond the institution. These fault lines are clearly visible; for example, the findings of a recent survey of Academy applicants and graduates shows to what extent studying arts [“freie Künste”] is viewed as a privilege largely assumed by those with an “educated family background,” EU nationals and those from an economically advantaged class. This non-egalitarian social distribution of opportunities could be related to the fact that “art” is traditionally conceived as a practice that operates outside of society, challenges its traditions and conventions and is carried out by certain subjects who only parasitically partake in the productivity of this society are thus to a certain extent privileged as well as expendable members of society. However, this is only one side of the coin. On the other side, in post-Fordism “art” or “cultural production” have emerged as key productive forces that certainly appear to bear less economic significance within a (practically booming) art market than when considered in terms of normative notions of “creativity,” “aesthetics” or “criticality.” These notions are closely associated with “art” while they also play a crucial part in the formation of the contemporary subject through which they again have an impact on society.

After decades of ideology critique and sociological analysis, it is no longer necessary to underscore the fact that “art” is not an autonomous, somewhat innocent zone. Nonetheless, and quite rightly so, one of the key critical figures within the protests within and around the Academy of Fine Arts was an awareness of the impossibility to describe or examine the events and problematic situation at an art school as isolated from the whole of society and ultimately from global socioeconomic and political processes. The critique of the endeavors to enact elements of the Bologna Treaty—and with it the school-like regimentation of university study and competition on all levels—was and is still linked to a critique of their entanglement of art universities like the Academy with global mechanisms of control and the logic(s) of exclusion and inclusion in migration, finance and knowledge transfer.

Suddenly racism, sexism, homophobia and animal rights were discussed within the physical and institutional spaces of higher education in the arts, spaces traditionally dedicated to producing emerging artists for the art industry, cultivating the ideology of individual creativity and securing originality as a valuable resource. All of which usually takes place under a premise that kindly asks us to overlook the social, political and economic conditions under which this dominant patriarchal-bourgeois-nationalist-western illusion is enacted.

Managing places to study at the university

If nothing else, the financial crisis has made the contours of numerous repressions, asymmetries and precarizations clearly stand out within the university context. Since 2008, “money” has become even scarcer than it already had been and on 4 October 2010, the Austrian daily newspaper Die Presse declared: “one year after the large-scale student protests, the Austrian universities […] are about to collapse once more.” These days, rumors of upcoming budget cuts are buzzing at the Academy of Fine Arts. In particular, staff costs are to be cut, which basically boils down to jobs being rationalized, contracts not being extended and an increase in the precarization of the overall working conditions.

The Austrian government has threatened to reduce the university budgets by ten percent by freezing them until 2013. With the thin fabric of university financing already stretched beyond capacity, this can only mean that radical cuts will be made in the most delicate and at the same time most readily accessible area: teaching. Simultaneously, there have been reports that Austria has supposedly yielded three billion Euros in tax revenue. Regardless if this is actually the case or not, such a flagrant discrepancy must indeed be addressed and scandalized by those within the political arena. So now, all of a sudden, even the universities’ rectors have publicly and with much media attention, begun to mobilize against the Ministry’s grim plans.

This has not been done without calculated intention, as they have consciously picked up the energy of the unfavorable protests initiated by students, teachers and researchers in 2009/2010. Although most of the university directors’ agendas are transparent, they differ considerably from the protesters’ demands for a systematic expansion rather than limitation of educational opportunities. Fully in accordance with the ideal image of an internationally competitive university, the establishment seeks to improve the facilities for those with a place at the university to ensure “excellence.” The groundbreaking innovation is the neoliberal model of “managing places to study at the university” or Studienplatzbewirtschaftung, as it’s called in Austria.[1] This term means nothing more than mandatory entrance exams (which incidentally most of the departments at an art school have always required) and appropriate financing through tuition, which, up until now—at least for EU citizens studying in Austria—has only been comparatively low. As a way of conveying the idea as socially just, this neoliberal higher education policy invented the pleasant-sounding yet just as treacherous formula of “educational loans.”

In the wake of rhetoric of improving “facilities,” the seemingly neutral principle of “quality” is introduced. By combining the media hype of the horrifying imago of overcrowded classrooms “filled with the masses” where students have to sit on the floor—which are not circumstances conducive to creating “quality”—with the actual and often publicized accounts of the stress and excessive demands students and teachers face, solutions seem to come about on their own. The discursive and political construction of the proof of the situation can only lead to one conclusion: to limit the number of students. This strategy is presented along with populist images that show, for example, that the taxpayer is obliged to pay the same amount for the university education of a general manager’s son as of a daughter from a “socially disadvantaged” working class household. This is just one of the many striking “injustices” the neoliberal project co-opts.

Existence made naked?

Not only due to the budget plight, the dreams of bliss of the creative industries and knowledge economy (by the same token dreams of a successful career in the art market or art education) at the Academy of Fine Arts have given way to a certain sense of reality made up of existential fear, a sense of melancholy regarding the future, and anger. This is indeed visible from all sides and on all levels of the academic-professional architecture: from the students, the “non-professorial” teaching and research faculty to a considerable portion of the professors. There has been a notable increase in the sensitivity and irritability of those participating in and affected by all of this, in particular, their reactions to neoliberal phrases like “efficiency” and “excellence.” While the rhetoric of factual constraints may be potent and even make some of the university committee’s non-solidary decisions and reluctant job cuts appear somehow acceptable, at the same time, this particular rhetoric is systematically (made) transparent and thus receives the most exposure. The willingness to accept it as something that possesses any kind of truth, however, is quickly plummeting toward zero.

It has been repeatedly speculated as to why the 2009 protests originated at an art school. Could it be that the myth of nonconformity and a certain ontological rebelliousness predestines artists and cultural producers to raise an alarm and demonstrate their dissent? Is there anything that would meaningfully infer that the art school, along with its proverbial individualists and individual artists, could emerge as a context of resistance and the organization of dissent and critique? Moreover, isn’t the often berated “artist critique”—a discourse Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello deem responsible for network capitalism—not also a politically and socially productive force, one that is capable of bringing about concrete change, after all?

It’s probably wise to proceed with caution here and to differentiate between a “critique d’artiste,” i.e. one that calls for authenticity, subjectivity and spontaneity with its supposed contribution to de-politicizing and atomizing the workers, and a critique especially voiced by artists—a specific kind of academic, professional and culturally productive “immaterial” worker—who consider their own working conditions (including their studies) and simultaneously engages with other social struggles around justice, equality, visibility, antidiscrimination, antiracism, antisexism etc.[2]

In 1984, in one of his final lectures on the courage of truth and the government of self and others, Michel Foucault traced how artists in modernity perpetuated the tradition of cynical truth telling or parrhesia (fearless speech) through which modern art and its authors stripped existence to its bare elements. In the 19th century, the “art as the place of the irruption of the elementary, existence made naked” i.e. Manet and Baudelaire, and later Beckett and Burroughs, brought about a kind of “anti-Platonism” that laid the foundation for a particular kind of polemic relationship that art establishes “in culture, […] with social norms, with values and aesthetic canons.”[3] Through its “permanent Cynicism regarding all established art,” and of all established forms, modern art fulfills an “anticultural” function. “[T]he consensus of culture is to be confronted with artistic courage in all its barbaric truth. Modern art is Cynicism culture, it is the Cynicism of culture that turns against itself.”[4] This image of the truth-seeing cynical artist who throws cultural protocol to the wind and exposes the core of historical problematizations of issues may have always had an air of the improbable and counterfactual. Nonetheless, it cannot be ruled out that this idea continues to affect and inform the subjectivities of art students and teachers today.

Scritti Politti

This is not being said out of the pure pleasure of speculation but rather, among other things, based on the historical familiarity of some of the statements and actions during the protests. Taking a look at the pamphlets and analyses of the students at British art and design schools during the 1970s, for example, we can see a striking resemblance to the announcements, flyers, posters and stickers that were in circulation in the fall of 2009. This challenging of academia with its tenures and rituals, the systematic disavowal of career-mindedness, the critique of a ranking mentality that completely lacks solidarity, the flouting of merchantability, the denouncement of any form of neoliberal conformity, etc., which were characteristic of the protests, also appear to be a continuation of a certain criticism and mode of critique developed at British art colleges between ca. 1976 and 1979, during the punk and post-punk era.

Especially the representatives of the Student Community Action Resources Programme (SCARP), an organization founded by students and young staff members who sought to politicize the situation at various art colleges throughout England and Scotland, applied a concise, activist-militant form of analysis. Dave Rushton and Paul Wood had a hand in generating and coordinating a great deal of the critique of the various art education reforms in Great Britain since the 1960s. They had been students at the Lanchester Polytechnic, Coventry and at the Newport College of Art in the early 1970s and began teaching in the mid-1970s as young lecturers of a second generation of authors and artists related to the Art & Language group. Their inquiries primarily sought to challenge the conservative, proto-neoliberal backlash, at first spearheaded by Margaret Thatcher, which also began to affect art education policy in the early 1970s. A central project of the conservatives was to dismantle tendencies towards an egalitarian-meritocratic opening of the universities, colleges and polytechnic colleges introduced in the 1960s. According to the right-wing, the diagnosis was plain and simple: too many people were accepted to study at higher education institutions and were therefore not available to serve the economy as cheap, uneducated labor.

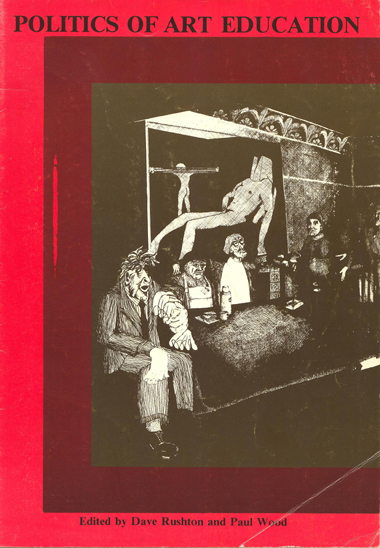

Cover image: Politics of Art Education, Dave Rushton and Paul Wood (eds.), London 1979 (Design: School Art/Edinburgh)

Rushton and Wood’s detailed study Politics of Art Education published in the late 1970s, dealt with the “expansion” of education in the 1960s up until the Tories put an end to it with their educational policy measures. According to Rushton and Wood, the opening of the educational institutions had not at all been “value-free” or “progressive,” as it was so often presented. On the contrary, the educational policy measures were to be understood as a social-democratic “means towards ameliorating a specific organization of production.”[5] Rushton and Wood uncovered both the functionality of the 1960s educational reform (particularly for actors in art and design, who were the addressees of their study), as well as the Tories’ reinstatement of the hierarchy between universities and polytechnics, and their reactionary, pro-business diktat that meant subordinating the sciences, design and art to the industry’s interests. The conclusion Rushton and Wood came to in 1977 was annihilating: “that ‘teaching’ in design largely reduces to students receiving a mixture of technical expertise and management training, prior to entering ‘wealth creating’ industry: propping up capital as either management strata in large corporations or risk-taking entrepreneurs plugging monopoly’s leaks and egged on by high stakes – new tycoons. While ‘art’ education in turn fulfils the function of producing willing sub-social workers, increasingly the sons and daughters of the bourgeoisie, going out amongst ‘the people’ to distract them from any transformatory self-activity, with sophisticated and harmless cultural deflectors.”[6]

Two students from the Polytechnic Leeds showed how this could indeed be done differently. In 1977, Tom Soviet (né: Morley) and Green Strohmeyer-Gartside, together with fellow student Alan Robinson, wrote a trenchant report on the restrictive ideological situation at their college, which also appeared in Politics of Art Education. In a system of “repressive omission” hegemony is engendered on the basis of unclear criteria, gaps in definitions and stereotypical discursive patterns a “remarkable ignorance, indolence and pathetic helplessness” had been entailed among Leeds students, the authors claimed.[7] Their experiences with the frustrating educational situation led to them leave art school and the field of art altogether.

Soviet and Gartside were also criticized for their disclosure. They were accused of not offering any other real alternative; at best, they had offered an uncertain state of limbo. Their response was that there were ways to expose “the internal mess of the course” at art schools and thus contribute to a restructuring that could be more beneficial to society. They had simply decided to go a different way themselves: “Those of us who are committed to bringing about changes in attitudes, provoking useful questioning, have already discarded the old tools of art making, and are looking for and using more successful methods which achieve our aims (at the moment this includes being involved directly in political work, performing overtly political music in a punk rock band, setting up conditions to compile and print an art theory journal).”[8]

Excerpt from the advertisement pages in Politics of Art Education, which also include adverts from Socialist Review and St. Pancras Label/Rough Trade (for Scritti Politti), 1979

The punk band was called Scritti Politti and was conceived more as an interdisciplinary “project” than as a conventional rock band. The name paid tribute to the title of a collection of political writings by Antonio Gramsci, though they had changed the Italian “politici” to “politti” (as in “polity”). The titles of the raw, reggae-inspired songs from their first two albums in 1979 included “Messthetics,” “Hegemony,” “Scritlocks Door,” “OPEC-Immac,” “Bibbly-o-Tek,” and “Doubt Beat.” Scritti Politti and Green Gartside were soon to become one of the most successful acts of 1980s intellectual post-punk-pop, and an enlightened version of all the art school graduates who had drifted from art education towards pop music culture, which British pop history is famous for.[9]

Breaking with the ideological systems of art and art education could also result in the formation of a political punk band nowadays. It is perhaps this comparable “mixture of blatant selfishness and easy social conscience” combined with a loathing for this mixture that creates such a rift.[10] Within art academies, however, the critique of systems that repressively omits critique in the name of individual self-realization currently aims to challenge new forms of subjectification, forms in which a project-like quality and criticality are fixed components and where truth-telling is confronted with an already/always-knew-that attitude. Regardless of this, the initial basis for resistance and organization is still the analysis of the ideological and social functions of art education, which is to obscure racist, sexist and homophobic patterns of inclusion and exclusion in addition to the class-based structuring of artistic and educational practices. In the “flabby, liberal mess” that was pivotal to Green Gartside’s and Tom Soviet’s decision to leave the field of art in the late 1970s, the government had already begun producing subjects capable of functioning in an economically driven, deregulated everyday life. Especially in a country like Austria, the urgent demand for “excellence” and money to feasibly “manage” the number of places to study cannot be set apart from a discourse of nationalist-immigration policy eugenics (articulated by differentiating between desirable and undesirable migrants and thus also between desirable and undesirable students). The continuation of the 1970s “politics of art education” would therefore entail developing a political economy of art and producing subjects for the cultural institution by engaging with these interconnections while still allowing for cynical truth-telling—which incidentally took place repeatedly during the protests and occupations in the weeks and months following October 2009. Such a cynical-political economy would also be equipped to show that bringing up problems is something other than radically challenging the problematizations that are at the root of the problems. These also appear, for example, in the seemingly unavoidable normativity that “quality,” “excellence” or “competitiveness” engender (in the distribution of places to study at the university or of funding for research). Challenging things in such a way may also call for a radical transformation of praxis as well. How about (making) a punk single (or something like that) for a change?

Digital Locks, Part 2

The digital locks on the doors of the main hall of the Viennese Academy presented above aren’t any after all. Or better yet, they have no physical locking function—they are purely symbolic. They are trompe l’oeils, stickers with a deceptively realistic outward appearance (fastidiously imitated traces of abrasion and grease included). Whoever put these stickers up has a clear understanding of a way of anticipating the future that became the present long ago.

[1] Translator’s note: The German term Bewirtschaftung not only means management, it also carries with it a notion of a “rationing,” connoting a restriction of the number of places available for studying at the university [Studienplätze].

[2] Cf. Maurizio Lazzarato, Mai 68, la “critique artiste” et la révolution néolibérale à propos de Luc Boltanski et Ève Chiapello, Le Nouvel Esprit du capitalisme, in: La revue internationale des livres et des idées, no. 7, September-October 2008, http://revuedeslivres.net/articles.php?idArt=271&PHPSESSID=2418f315788c7349762195ab6780f645

[3] Der Mut zur Wahrheit. Die Regierung des Selbst und der anderen II. Vorlesung am Collège de France 1983/84, p. 247.

[4] ibid, pp. 249.

[5] Dave Rushton/Paul Wood, Section Four – 1970 to 1977 [1977], in: Politics of Art Education, ed. Dave Rushton and Paul Wood, London: The Studio Trust, 1979 [a School book], pp. 29-44, here: p. 34

[6] Here, Rushton and Woods are playing on the discourse and cultural-political praxis of ‘community arts,’ which the British Arts Council had set out to fund in the early 1970s. The idea was that artists would make an “impact on a community by assisting those with whom they make contact to become more aware of their situation and of their own creative powers.” In doing so, the Council had hoped “to widen and deepen the sensibilities of the community in which they work” in order “to enrich its existence“ (Community Arts, in: Report of an Arts Council Working Party, Arts Council Great Britain, June 1974, quoted in ibid., 42).

[7] Cf. Alan Robinson, Green Strohmeyer-Gartside, Tom Soviet, “Show Us Your Uniqueness” [1977], in: Politics of Art Education, pp. 44-50, here: 48.

[8] Tom Soviet/Green Strohmeyer-Gartside, Whatever Next?, in: The Noises within Echo from a Gimcrack, Remote and Ideologically Hollow Chamber of the Education Machine: Art School, (eds.) Dave Rushton und Paul Wood, Edinburgh: School, 1979, pp. 89-91, here: p. 91.

[9] For more on this see: Simon Frith/Howard Horne, Art Into Pop, London: Methuen, 1987.

[10] Ibid, p. 90.