09 2025

May See Dreams More Queerly

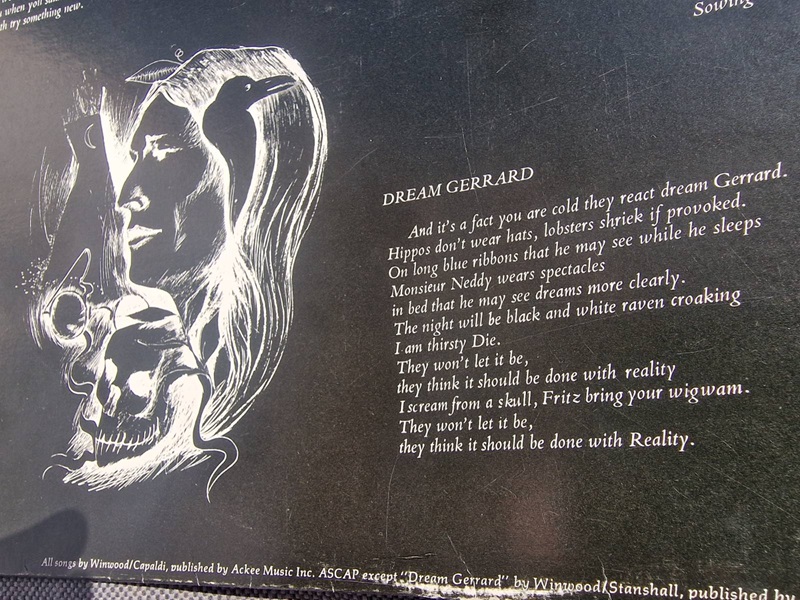

I. Dream Gerrard

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q1VWMkbpsqU

The queer is dividual, never bound to an individual. There is no queer identity: the queer is anti-identitarian and becoming similar. It is not substance, always subsistential, always in something, under it and around it. In this respect, messy hair can be queer antennae, open arms, feelers that are attracted and touched by other hair and arms and feelers.

In March, we drove to the Portuguese border and bought a second-hand Rhodes E-Piano Mark II. It was manufactured in the thirteenth week of 1981. Around 1981 I had a Fender Rhodes, a Mark One from 1974, which was already hard to play at the time.

While the new old electric piano is being renovated over the summer, I'm exploring the small record collection for records from that time on which a Rhodes is used. Rhodes pianos with phaser, chorus or tube overdrives, Rhodes pianos in the songs of Grover Washington Junior, Roberta Flack, Herbie Hancock, in Stevie Wonder's Songs in the Key of Life, Riders on the Storm, with Billy Preston as the fifth Beatle on the LP Let It Be, and finally in the Traffic album from 1974, When the Eagle Flies.

On this album, which Traffic recorded on an 8-track machine in their own studio between July 1973 and June 1974, Stevie Winwood experiments with all kinds of keyboards, with Moog synthesizers and the Mellotron, and with the Rhodes piano. This album also contains the song Dream Gerrard, which has always appealed to me: the combination of funky groove and psychedelic sounds, the title itself, the lyrics were completely lost on me, but at the time we were used to cryptic lyrics and nonsense, and besides, it wasn't so important to understand the English lyrics word for word. In any case, I obviously wasn't meant, but another Gérard, with a double r.

Winwood, who had started out as a fifteen-year-old boy wonder with the Spencer Davies Group in 1963, had risen to become part of the British rock establishment by the end of the 1960s and then developed into a star and mainstream pop musician. While to many of his fans the LP When the Eagle Flies seemed more like the decline and swan song of a supergroup, the late psychedelia of the album was always very close to me. Winwood's phrasing is influenced by his rhythm & blues experiences with the Spencer Davis Group, plus that funky rhythm and a dose of soul, but the lyrics are pretty arty even by the standards of the time, the vocal line interrupts units of meaning and even words and rearranges them, and you don't really know whether Winwood knows what he's singing when he sings "Dream Gerrard."

He had co-written the song with someone else. In derives through various obscure channels, I found out who Vivian Stanshall was: perhaps the most peculiar representative of a whole generation of music-making art students in 1960s Britain, in London between Central St Martins and Goldsmiths. Vivian Stanshall did not invest in the developments of psychedelic and progressive rock, and was always a little more innovative than his musical surround during his time with the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, working between commedia dell'arte, music hall, and anarchic performance. Yet, as an English Dadaist or Neo-Dadaist, he was also suspicious of innovation and originality. With the Bonzos, he didn't try to be original but instead stretched fragments of existing musical forms with monstrous, surreal poetry in a style quite volatile. Their props and puppet machines, grotesque costumes and absurd theater influenced the Monty Pythons avant Monty Python, the late Beatles and the early John Peel, not simply as stage outfits and performances, but by more and more often flowing directly into everyday life in order to denormalize it, to deterritorialize it, to bring it a little out of joint, out of the furrow. [1]

In the early seventies, it all somehow got stuck, peculiarly localized, as English humour, which probably also subverted itself consciously in order to avoid too wide a dissemination and international marketing. But the overlapping underground and bohemian lifestyles, the specific aesthetics of existence after London became swinging, led to ever new social machines and musical collaborations. What was peculiar about the British 1960s and early 1970s was that there were strange and persistent overlaps between socialities and milieus, such as that of the freaky, camp and anarchic neo-dadas and doodahs who had outgrown their art academies and a rock scene, to which Steve Winwood belonged, that was not yet quite so polished and still open in terms of style.

In 1973, two biographies of Gérard de Nerval were published in English by Norma Rinsler and Benn Sowerby[2], and Vivian Stanshall read at least the second one, probably finding many parallels to his own restless and unruly life: the fragile relationship with a father returning from war, the existential unsteadiness, the experimental artistic forms, the craziness of everyday life, the mental breakdowns - all of these are overlaps between Vivian's and Gérard's lives across the centuries. Dream is a second life, the motto of Gérard de Nerval's last novel Aurelia. The Dream and the Life from 1854, had a strong impact on Vivian Stanshall. And ultimately it also led to the central message in the refrain of Dream Gerrard, which deplores the fact that the transitions between dream and life are suppressed in favor of a limited concept of reality: They won’t let it be, they think it should be done with reality. From the concatenation of dream and life, as in the subtitle of Aurelia, to making impossible, repressing, clashing this very threshold, this joint, the vagabondage between dream and life.

In just a few lines, Stanshall’s lyrics cast four spotlights on the life and writing of Gérard de Nerval – 1., on the relation of life and dream, 2., on the life forms of the bohème galante, 3., on Nerval's writing style and aesthetic technique, and finally, 4., on his death. These are all points of reference from the Nerval biography The Disinherited by Benn Sowerby, which Stanshall could easily link to his social surround and the aesthetics of existence in the 1960s and 1970s.

1. And it's a fact you are cold they react dream Gerrard.

The introduction, like the refrain, focuses on Gérard de Nerval's central theme and technique, the play with all possible thresholds, all possible transitions from and into the dream, from daydreaming to hallucination. Dream Gerrard is the dream that Vivian dreams together with Gérard in this song, but also Dream-Gerrard, the transversal intellect, the dividual crowd of ghosts writing with the poet Nerval, his social surround of the bohème galante in the 1830s, those that he translated, from Goethe to E.T.A. Hoffmann to Heinrich Heine, the formative female figures of his life and his texts, from Pandora to Sylvie to Aurelia, and perhaps even us in a queer present, who revisit the minor stories of long-past aesthetic and political struggles fifty years after Traffic and Vivian Stanshall.

2. Hippos don't wear hats, lobsters shriek if provoked, on long blue ribbons ...

sums up the eccentric actions of the bohème galante in the 1830s in two short formulas, which are drawn from the wealth of anecdotes in Nerval's biography: Gérard is in his 20s, and he enjoys going to the Jardin de Plantes: "There he stood for some time watching a hippopotamus in a pool. Finally he threw his hat at it and went to visit the paleontological galleries."[3] Vivian Stanshall transforms these sentences from the biography into the short version hippos don't wear hats. In the song lyrics, the hatless hippos are supplemented by another animal species and an early form of flâneur, and the biography says:

"... he had appeared in the Palais-Royal arcades leading a lobster on a ribbon, and, when questioned, had replied: ‘Why is it more ridiculous to have a lobster to follow one than to have a dog or a cat, a gazelle, a lion, or any other beast? I like lobsters: they are quiet and serious, they know the secrets of the sea, they don't bark, and they don't devour one's substance like dogs, which Goethe found so antipathetic, and moreover he was not mad!’"[4]

Mad or not, for Vivian Stanshall these references to the bohème galante and their weird performances in Paris in the 1830s were directly linked to the spontaneous appearances in the everyday life of London pubs and clubs in the early 1970s and to his own pranks, and one can imagine that Tosquelles would not have been entirely averse to such fun with his surrealist friends in the 1940s.

3. That he may see while he sleeps Monsieur old Neddy wears spectacles in bed that he may see dreams more clearly.

Monsieur old Neddy is Gérard's friend, the poet Theophile Dondey, who anagrammatically changed his name to Philothee O'Neddy and was so short-sighted that he always had to wear spectacles. The biography reads, "He would even wear them while he slept, for he said that without them he ‘could not distinguish his dreams and lost all the enchantments of the night.’"[5] So it is not necessarily the idea of analysis or dream interpretation, or of x-raying the dreams in order to unearth a normality of dreams that lies behind the desire for clarity, to see dreams more clearly. What drives O'Neddy and Vivian Stanshall to wear glasses when sleeping is much more the fear of missing out on the magic of the night, on its enchantments, of not seeing queerly enough without glasses. The queer vision of dreams harbors the magic of the night.

But the night not only has its enchantments, it will be black, and white, sleepless:

4. The night will be black and white raven croaking I am thirsty Die

The biography reads: "On 24 January [1855] he wrote to his aunt, ‘... Do not expect me this evening, for the night will be black and white’."[6]

A white night, une nuit blanche, a sleepless night, and it is also a black night, at least this night in which Gérard de Nerval puts an end to his life. And the croaking raven is reminiscent of the poor malade from Aurelia, who the first-person narrator calls brother and who, on the last page of the novel, awakens from his coma thanks to Je-rard’s attention and says: “I am thirsty.”.

For all the concrete experience of suffering in Limbo: the queer magic of the night is an attack on normalizing discourses and an indication that the boundary between art and delirium remains threatening for all parts, inwardly towards its subjects, but also outwardly as a component of molecular revolutions.

There is one more sentence between the refrains that cannot be unraveled directly and explicitly in the biography. Fritz, bring your wigwam. I interpret it as a figure of vagabondage that traverses Nerval's life, desires, and works. Fritz is the Germanophile Gérard de Nerval, who at the end of his life always carries his belongings with him, his home, his subsistential territory, pitching his tent wherever he happens to be. The biography notes about Nerval’s last year of life:

"Since he had left Passy he had no permanent residence. [...] His vagrant nature had reasserted itself. As so often before, he spent whole nights wandering about Montmartre, the markets and the suburbs, sometimes mingling with sordid company in the cheapest all-night taverns frequented only by the poorest laborers, thieves, prostitutes and vagabonds. He slept little, and wherever occasion provided. During the day, too he wandered about the city in search of inspiration or sat in a café with the blank paper before him."[7]

And this is what Vivian Stanshall explains about writing Dream Gerrard with Steve Winwood and in a similarly volatile situation: "I was suffering a severe bout of depression when I was staying at Steve's house, and he said, ‘We're off to dinner. Are you coming?’ I said, ‘No, I'm reading about this French poet and I don't feel very well.’ So he went off and I wrote not more than a quatrain about Gérard de Nerval. When he came back, he said, ‘Right! That's a chorus. We need a verse for that.’ And he went into the front room and started plonking away on the piano."[8]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JCSUgawzDG8

II. The queer deliriums of Gérard de Nerval

1. One hundred years before Surrealism and Art Brut, which would briefly intersect in Saint-Alban with the social machines of asylum and resistance, Gérard de Nerval invents a realism of dreams in manifold facets between delirium and poetry. Despite the softness of his minor masculinity, he does so with incredible sharpness of radical-realistic observation and description. Thus the dichotomies of dream and life, reality and delusion transform into an affirmation of manifold hallucinations, visions and machinations, of the many ghosts that populate poetry. In Nerval's polyaesthetic light-footedness and enchantment, affirmation and differentiating, condensing description do not arise in two separate states of dream and life, but in a multiplicity of shades that want to be written and read with the intensity and precision appropriate to them.

“The dream killed life,” wrote Nerval's friend Theophile Gautier in his obituary after Nerval's suicide in January 1855[9], but in Nerval's life dreams were rather a vast land of material for his radical realism, leaning towards lived experience. Gautier's interpretation is too much shaped by the end, by an end that had admittedly been plagued by fears, seizures and breakdowns, by precarity and homelessness starting in the 1840s and intensifying in the 1850s. Gérard's legacy, however, is: "The dream is a second life." This is how he begins his Aurelia, whose subtitle is not The Dream and the Life for nothing. And it is not just dream in the narrower sense – what resounds through and illuminates this vast land of delirium, is half-sleep, daydream, waking dream, imagination, illusions and visions, hallucinations and hallos, hearing voices and having second sights.

The first drafts of Aurelia probably date back to Nerval's first breakdown and hospitalization in February 1841. This was preceded by real or imagined love dramas with the celebrated actress Jenny Colon in Paris and the star pianist Marie Pleyel in Vienna, which even overlapped in Brussels around the end of 1840 and beginning of 1841. In this respect, the figure of Aurelia is not to be understood as an identifiable female individual from Nerval's biography, but always as a constellation of a multiplicity of real and mystical female figures. In the first part of Aurelia, Nerval describes the first phase of what he calls his vita nuova, stumbling over the idea of calling it an illness: "and I don't really know why I call it an illness, because I have never felt better for myself."[10] However, he elaborated it only after a further stay in the clinic in 1853, during the last year of his life, as the conclusion of the (second) phase in which, from 1852 onwards, he wrote some new things, reassembled others and published the books that established his fame as the secret hero of the avant-gardes of the early 20th century. This is also the period in which he realized that he could no longer fully control the influx of dreams into his life and the increasingly violent experiences of crossing boundaries.

After the first introductory pages of Aurelia - the first-person narrator has just returned from the Aurelia/Jenny-Marie constellation in Brussels to Paris planning to "hurry back to my friends"[11] as soon as possible - one form of delirium follows another in quick succession: the second sight in the daydream is followed by a long nightmare, and the following evening by a series of delusional visions, including a seizure and a fall, which ends with a long stay in a clinic. Even if Nerval's confident descriptive and narrative style has changed with Aurelia into an often shaken and worry-driven vulnerability, his aim remains to be able to see dreams more clearly through radically realistic description. This clarification and elucidation of dreaming results in affirming and differentiating even the most drastic events and delusional scenarios. Wearing glasses while sleeping in order to "see dreams more clearly" corresponds to the narrator's radical-realistic spectacles in Nerval's descriptions of experienced and imagined landscapes, relationships and dividual thing-worlds.

2. What would transform into homelessness, extreme precarity, and disorientation in the last years of Nerval's life was, in the early 1830s, the open testing of an experimental way of life: the aesthetics of existence of the Parisian bohème galante, as Nerval called it in the title of a volume of poetry twenty years later. An unruly artistic life in a dilatated present that draws its models from the vagabond lifestyle of what Marx would denounce in the Eighteenth Brumaire as lumpenproletariat. As far as travelling and vagabonding are concerned, Nerval's bohemian phase of the early 1830s is about the city and strolling, but later also becomes an escalating travel activity that can be understood as both a moment of unrest and deterritorialization, and as the territory of a material that could be literarized in ever new layers. This applies to the trips to the Orient as well as to the journeys to neighbouring Germany, the childhood landscape of Valois, or the surroundings of Paris.

In November 1834, Nerval wrote to a friend: "My address is now Impasse du Doyenné no. 3, but I am hardly ever there. That means that as long as nothing has been arranged, I spend the night on a mattress and wait for things to improve."[12] Fritz always has his wigwam with him strolling through the Parisian bohème, appropriately with the address Impasse du Doyenné: settling down in derelict districts, in cul-de-sacs between misery and feast, sleeping on mattresses, strolling with or without lobster, throwing hats to the hippos.

3. Throughout his life, Nerval always experimented with modes and genres of writing: travelogues, dramas, short stories, translations, poems, prose poems, portraits, essays, literary criticism, journalistic articles, anthologies compiled or recompiled from existing texts, novels and novellas such as the works Sylvie, The Daughters of the Flame, The Illuminati and the last novel Aurelia, which were often seen as models for the avantgardes of the twentieth century. After an inheritance in the mid-1830s and brief years of squandering this money in an altruistic rather than narcissistic manner - "We were young, always happy, occasionally rich" - the precarious phase of Nerval's life begins in the early 1840s: socially and psychologically as well as materially, and this also means that he switches between genres depending on demand. Nerval's practice of cutting up, fragmenting, tearing apart, of repackaging, recycling, reassembling and reselling existing fragments arose out of necessity, when in precarious situations, from lack of money to phases of delirium, he must produce according to the situation – and quickly. But at the same time, though out of necessity, a style and a literary technique of dissociation emerge, of finely chiseled leaps and breaks that do not want to join despite or precisely because of their exact jointing, as dissemblages and deconnages.

Most of Nerval's texts are very precisely conceived, and yet at the same time they are characterized by a lightness that leaves all pathos behind, sometimes even commenting with self-irony. Heinrich Heine wrote: "Gérard's language flowed with a sweet purity that was inimitable and resembled only the incomparable softness of his soul": "an angelic being,"[13] whose gentleness, shyness, attentiveness and sociality were combined with keeping a low profile and a certain reserve. This reserved attentiveness of a minor masculinity is mirrored in the precision and tendency towards the things that Nerval describes in his texts and handles with virtuosity, in fragmentation and recomposition.

The recomposition and refiguration of the texts is also about the inner-textual process of playing with multiple and alinear temporalities. Flash forwards, flashbacks, combinations of times and confusion of tenses. His virtuosic and tumultuous handling of layers of time often leads to dizziness when reading, to the need to turn back pages and try to ascertain how exactly one thing is interlaced with another. And even with all the turning back pages and searching for balance, there is still a remnant of vertigo.

An example of the unruly handling of time layers from the novella Pandora from 1854. Over New Year's Eve 1839-40 in Vienna, Nerval stays for three months in a small room "with laundresses" in Leopoldstadt. Pandora appears to the first-person narrator here in the contemporary guise of the pianist Marie Pleyel, who has invited him for New Year's Day. He drinks his way through the Silvester evening alone and spurs on his nocturnal waking dreams with a red Tokay and a Bavarian beer and finally with a mug of Heurigen mixed with a mug of old wine. Marie/Pandora then transforms into Empress Catherine of Russia, and things accelerate into a game with eternity, which threatens to have an expiration date in the confusion of the course of times, as Pandora pollutes the air with her poisons - "'Unblessed!', I said to her, 'through your fault we are lost, and the end of the world is at hand!'" But here, too, the end of the world appears rather as a possibility that threatens the individual: the first-person narrator fails to keep up with the goddess soaring up into the thousands or even millions of years foreseen for her, and instead occupies himself with devouring a few pomegranate seeds, chokes, threatens to suffocate, then his head is cut off, "and I would have been dead in all seriousness if a parrot passing by quickly had not pecked up some of the seeds I had spat out." A slightly different case of metempsychosis, and the parrot takes the seeds, mixed with the first-person narrator's blood, to the Vatican. And so on.[14]

4. Nerval's delirium is not delirium of domination, but "bastardly delirium" (délire bàtard, as Deleuze calls it in Critique and Clinic[15]), and I would add, disorderly-queer delirium, in the sense of the Latin de-lirare, 'to get out of the furrow', 'to deviate from the straight line'. Furrowing normalization is the problem, de-lirium insofar means queering deviation, escaping from the normal, a minor life out of joint, as deviance and delirium of dissemblages.

In the final pages of Aurelia, the clinic proves to be a place of inspiration for the first-person narrator at night, and the gentle company of the poor malade during the day. "The poor fellow, whose intellectual powers had so strangely retreated," receives Gérard's caring attention: "After I had learned that he was born in the country, I spent long hours singing old village songs to him, in which I tried to put the most touching expression." At some point, the malade begins to sing along, slowly opens his eyes and finally says: "I'm thirsty."[16] What seems to go hand in hand with death in Vivian Stanshall's lyrics of Dream Gerrard, in Aurelia turns out to be a social machine, affirming dissemblage, deviation, denormalization. Of course, the malade thinks he has died, believes he is in purgatory, but the dividual delirium, the ethico-aesthetic intervention, the social machine and its instituent care make him sing, and who knows, bring him to new life.

Gérard de Nerval is often confused with the first-person narrator in his stories. In the worst case, this confusion results in an unambiguous gender identification of Nerval as an unhappy, loving man who has fallen for an unattainable woman and universal mother. This reductionist interpretation exists in literary studies and psychoanalysis. But it does not do justice to either the author or his female characters. Sylvie, Pandora, and Aurelia are situated and singular figures, who nevertheless almost always remain strangely dark and merge into one another in their outlines. They are unfurrowed-disorderly figures that cannot be fully individualized and identified, and whenever they seem to become tangible, they fade into fog and darkness, into multiplicities and constellations of different "daughters of fire."[17] On the one hand shadowy intangible, on the other dangerous with the precision in details typical of Nerval, strong with Nerval's own respect for the specificity, situativity, and singularity of his (female) figures. This is the primary feminist quality of Nerval's writing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aGDbZU9OZRU

III. Tosquelles as Queer Dividual

In April, I drive to Saint-Alban, and the young woman who manages the tourist office in the old buildings of the asylum, who I ask about archives on Tosquelles, refers me to the departmental archives in Mende. I am again delighted by the butchy coarseness of the women in the tobacco shop in Saint-Alban, which is also a souvenir store and a bookshop, and as I shuffle through the short aisles, I am visibly eyed as a potential thief and buy the same Tosquelles book as last time. Then I drive to Mende and first come across locked doors, not because I'm ignoring the opening hours but, if I understand correctly, because of the terror alert three months before the Olympic Games. With a little patience, however, the doors open and I can make myself understood with all kinds of broken languages. With the help of the Cerberus secretary, the friendly librarian, and the reserved yet courteous archivist, I manage to get hold of several finely knotted packages of documents, and I fail to return them just as finely knotted. They are contradictory series of documents from the period in which Tosquelles is writing and defending his dissertation on the lived experience of the end of the world and Nerval’s Aurelia.[18]

The handwritten note by a policeman with an illegible signature dated April 29, 1942 contains the statement that "Dr. Toscalès" had "an extremely negative influence on the entire staff of the hospital," "clearly revolutionary and anti-national tendencies."

About one year later, the "Report on the political situation in the municipality of Saint-Alban to the Prefect of Lozère” is dated April 8, 1943: In it Police Commissioner Rispoli from Mende reports about the suspicion that “a dull anti-national agitation was manifesting itself in […] the psychiatric hospital” and about “a number of people whose loyalty to the government and the regime is highly questionable, who do not hide their sympathy for the Anglo-Saxon forces and who impatiently await […] the return of the republic and a ‘popular front’ government."

The longest part of the report is devoted to:

"Tosquellas-Llaurado Francisco, born in Reus/Spain, married to Alvarez-Fernandez Helene, has two children, aged seven and one, who all live with him. A doctor of psychiatry in Spain, he was mobilized into the Spanish Republican Army during the Civil War as a lieutenant doctor and later captain doctor. In September 1939, he fled to France and was interned in the Septfonds camp (Tarn et Garonne).

On January 22, 1940, Tosquellas was assigned to the psychiatric hospital of Saint-Alban as a nurse at the request of the head physician of the institution, which was short of doctors due to the war. […] From a professional point of view, he is very satisfactory. Cultured and fluent in our language, Tosquellas rarely leaves the municipality or even the hospital. […]

However, it should not be forgotten that Tosquellas was only assigned to Saint-Alban's hospital to compensate for the lack of management staff at this institution when many French doctors were mobilized. If the relevant circles decide that this situation has not changed since 1940 and the number of doctors is still too low, I think Tosquellas can stay in office. Otherwise, there is no reason to keep a Spaniard who is not tied to our regime and to whom common law should then be applied."[19]

Tosquelles had to remain in this dangerous position for more than a year after the police investigation, until the liberation, always under threat of being exposed as a member of the Resistance or simply no longer defined as indispensable for the clinic. Shortly after the end of the war, in 1946, he began the lengthy process of naturalization, for which, as Oury points out in his preface, his French dissertation would also become relevant.[20] In addition to emphasizing his excellence as a physician, the possibility of making him head of a clinic, and his assimilation to French customs and institutions, the same police department that had proposed his deportation less than four years earlier now attributed to him a concrete reason for naturalization: "During the occupation, he was very attached to the Resistance and is said to have cared for many young people from the Maquis, especially the wounded of Mont Mouchet."[21]

1. In 1948, the year in which the entire Tosquelles family successfully obtained French citizenship, Tosquelles submitted his dissertation entitled "Essay on the meaning of lived experience in psychopathology." On the one hand, the study is fed by multiple observations and records from clinical practice, which Tosquelles analyzes together with his colleague and boss Bonnafé and enriches with insights from the growing field of psychiatric reflection. On the other hand, it also builds on a specifically artistic presence in and around Saint-Alban: The extended visits of Éluard and Nusch, Tzara, Bonnafé himself, and later also Artaud, who Tosquelles visited before his death. Tosquelles wrote in Le vécu de la fin du monde dans la folie: "It was a matter of proclaiming and achieving a positive human understanding of madness outside the asylums. My illusion was of course maintained in Saint-Alban by the presence and interest of a number of writers, and even by their collaboration in our tasks. Paul Éluard in particular encouraged me in my endeavor by providing me with documents about Nerval."[22]

At the same time, the practice in Saint-Alban is also characterized by everyday artistic activities, which emerged and persisted before their identification and marketing as Art Brut, before the extraction of artistic practice from the social machine, and before the unambiguous branding as art of the mad or outsider art in the art field and among collectors.

In this constellation of experiences of anti-fascist resistance, vagabonding psychiatry and artistic experiments in Saint-Alban, an embodied knowledge emerges around the fact that artistic and poetic forms of expression cannot simply be read according to their content and interpreted psychologically.

While C.G. Jung still interpreted Aurelia in 1945 in a completely prosaic, non-literary way as an auto-nosological exercise that Nerval was told to do by his psychiatrist Emile Blanche and completed dutifully,[23] Tosquelles' reading can be understood as a complementary-subsistential reading that implicitly affirms the poetic aspects of the text. As a dissertation, Tosquelles’ text naturally had to satisfy the criteria of medical science, but it did not do so in opposition to Nerval's critical attitude towards the traditional clinic and his affirmation of delirium, or in opposition to his refined literary composition. Tosquelles writes: "Aurelia is not only a literary work, but an 'experienced document' of madness. We do no harm to the spirit of the work if we refrain from all aesthetic considerations in order to examine Aurelia as a clinical document. This is not a question of stigmatizing it with a nosological label."[24]

In a sense, this is not the opposite, but the flip side of what Anne Querrien quotes from Funció poética i psicoterápia, namely that we can consider “mad people to be poets who have not been able to make the indispensable poem out of their lives."[25] As Anne says, this is not about the irrevocable separation of mad and not-mad, but at the same time as this affirmation of fluid transitions, there is always a need to differentiate the subject positions, the social fields and, even more, the usages and modes of subjectivation and relation that are actualized here.

2. This can also be subsumed under the concept of aesthetic existence, which Tosquelles thematizes in Le vécu de la fin du monde dans la folie, aesthetics as the invention of new modes of subjectivation as well as new forms of living (together). Before turning to Nerval's text, Tosquelles writes a whole chapter on the "sphere of aesthetic existence according to Kierkegaard" and the "form of life of certain mentally ill people"[26]. Tosquelles refers to Kierkegaard's concept of the "spheres of existence"[27] and specifically that of aesthetic existence. "In aesthetic existence, one lives in an affective confusion of ego and world."[28]

"If one enjoys all possibilities by actualizing them, one lacks all power over oneself. One recognizes oneself only darkly. The aesthete cannot achieve 'self-affirmation' or self-acceptance. The self seems unreal to a certain extent. One lives in innumerable moments and plots. One feels liberated from all continuity of life, but the self that experiences and sees itself in this way is an enigmatic, depersonalized self."[29]

One can place this theory of depersonalization in aesthetic existence, like Tosquelles, in the clinical context of schizoid seizures and schizophrenia, but I would pose the question more generally as a search for experimental, unruly forms of life and subsistential territories, for the transversal machines between these territories, and for the molecular, condividual revolution. Which brings us back to vagabondage and Gérard de Nerval as Fritz, who is supposed to bring his wigwam with him.

Tosquelles reports on the examination of Dr. Barbier, who published the first clinical monograph on Aurelia in 1907, in which Nerval is described as an "alienated criminal," "because suicide can be described as the result of the criminal instinct." Quite apart from the scandal of this judgment, Tosquelles and we are rather interested in Barbier's diagnosis of manie itinerante, “which spread further and further and finally led to Nerval becoming a real vagabond."[30]

This is where we most clearly encounter the normalizing ideology of sedentariness, which identifies its outsiders as alienated criminals and vagabonds, be they travelling people, homeless city dwellers, or bohemian artists. In contrast, Theophile Gautier writes in his obituary of Gérard de Nerval:

"Although his appearance was often ragged, he was not in real misery. His friends' houses and their empty or full purses were also open to him when he was unable to work. How many of us prepared a room ten times in the hope that he would spend a few days there. No one could be prepared for longer, because his restless heart needed freedom! Like a swallow when you leave a window open, he entered, walked around twice, three times, found everything beautiful and charming and flew away to dream again on the paths. It was not indifference and coldness, but like the swift, the footless one whose life is an eternal flight, he could never stop."[31]

3. At a central point in Le vécu de la fin du monde dans la folie, Tosquelles explains his view of Aurelia in terms of genre: "In reality, Aurelia is a work that can be categorized neither as a novel nor as a memoir nor as a philosophical essay. Aurelia is poetry, experienced poetry. And this poetry, as Beguin says, decides the fate of its author."[32] Aurelia is poetry that actualizes the lived experience of delirium as a chain of events between dream and daydream, memory and hallucination. In the poetic recomposition, in the composition of the fragments, in stumbling over the breaks, the unspeakable is given its place. The craft of condensation, the rhythm of writing and the conscious technique of recomposing fragments of memory as a literary stylistic device create a dividual-machinic relationship in which the author and the swarm surrounding him wear many pairs of glasses, 4D glasses, hallucinatory glasses, psychedelic glasses. May they see dreams more queerly, and may queer here not be a subject, not a noun, but also not an adjective, but a stubborn adverb.

4. As great as the image is of the "queer" individual Tosquelles (as well as Stanshall and Nerval) with the messy hair, the often deviant language and the seemingly ingeniously created concepts, this individual perspective is not relevant to understanding the queer quality of the Tosquelles-machine. The queer is dividual insofar as it is not a queer identity. It is anti-identitarian and becoming similar. It is not substance, always subsistential, always in something, under it and around it. In this respect, messy hair can be queer antennae, open arms, feelers that are attracted and touched by other hair and arms and feelers.

Tosquelles writes, after a lengthy passage in which he expresses slight doubts about the abstractness of the collective unconscious in C.G. Jung: "the area of the human drama that we are considering takes place between personalities, and there is always an isolation within social life that characterizes it from the beginning. [...] The ‘individual’ has never existed. It is a borderline concept, even in pathological life. An abstract concept to which the ‘person’ ‘seems’ to regress."[33]

In one of his visions in the first part of Aurelia, Gérard sees a room flooded with light, fresh and fragrant:

"Three women were working in this room and, without exactly resembling them, they represented relatives and friends of my youth. It seemed to me that each of them combined the features of several of these people. The outlines of their figures changed like the flame of a lamp, and every moment something passed from one to the other; the smile, the voice, the color of the eyes, the hair, the figure, the familiar movements interchanged, as if they had lived the same life [...]."[34]

It is in this sense of dividual passing and interchanging that Tosquelles writes "Aurelia is not the real person of Mademoiselle Colon," she is a "’condensation’ of many women.”[35] Every interpretation as an unfulfilled or spurned or passed love for an individual and concrete person massively narrows the reading of the constellation. The singularities of Nerval's female figures remain dark enough, unstable and volatile not to be individualized. They retain their dividual quality, their temporal and spatial transversality, always several, always multiplicity, always constellation, ultimately queer, as at the beginning of Pandora, where Nerval writes that the beautiful Pandora of Viennese music theater would probably have been best suited to the riddle that could be read on a Latin inscription in Bologna: “AELIA LAELIA -- Nec vir, nec mulier, nec androgyna, etc. ‘Neither man nor woman, nor androgynous, neither girl, nor young nor old, neither chaste nor mad, nor modest, but all of these together’”[36]: Readable in both directions equally, AELIA LAELIA is a sign of the queer-dividual volatility of gender, but also of age and generations and the dichotomy of normality and madness. Pandora traverses all these attributions, queer in multiple ways.

And this manifold-queer constellation also shapes the authorship of Aurelia: firstly as Gérard, who obediently seems to write his medical report according to the clinical discourse, secondly as Je-rard, the first-person narrator, who obeys poetological principles and rearranges the narratives of dream and delirium, and thirdly and finally, as Dream Gerrard, the dreaming and dreamt-of dissemblage of transversal intellect as dividual authorship. And as components of this dissemblage, together with Aurelia, Pandora, Tosquelles, Nerval and Stanshall we keep denormalizing, de-liring, deserting the furrow, getting off track and out of joint, and we may learn to see dreams more queerly.

[1] See also John Roberts, Red Days. Popular Music and the English Counterculture 1965-1975, Wivenhoe: Minor Compositions, 2020, pp. 95-99; Lucian Randall, Chris Welch, Ginger Geezer: The Life of Vivian Stanshall, London: 4th Estate, 2010.

[2] Norma Rinsler, Gérard de Nerval, London: Athlone, 1973; Benn Sowerby, The Disinherited. The Life of Gérard de Nerval. 1808-1855, London: Peter Owen, 1973.

[3] Sowerby, The Disinherited, p. 130.

[4] Ibd., p. 81.

[5] Ibd., p. 27f.

[6] Ibd., p. 156.

[7] Ibd., p. 152.

[8] https://liberalengland.blogspot.com/2013/09/traffic-dream-gerrard.html. See also “Vivian Stanshall’s Week,” BBC 1974, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fq1Ndnr2HtQ&list=RDQMQjqvoEHcBYQ&start_radio=1.

[10] Gérard de Nerval, Aurélia et autres textes autobiographiques, Paris : Flammarion, 1990, p. 251.

[11] Ibd., p. 254.

[13] Heinrich Heine, quoted in Norbert Miller, “Nervals bukolische Hadesfahrten,” in Gérard de Nerval, Die Töchter der Flamme. Erzählungen und Gedichte. Werke III, München: Winkler, 1989, pp. 601-668, here p. 668.

[14] Nerval, Aurélia, p. 201.

[15] Gilles Deleuze, Critique et Clinique, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1993, p. 15.

[16] Nerval, Aurélia, p. 314f.

[17] Les Filles du feu is the title of a collection of short stories and poems by Gérard de Nerval.

[18] François Tosquelles, Le vécu de la fin du monde dans la folie: Le témoignage de Gérard de Nerval, Grenoble : Éditions Jérôme Millon et Jacques Tosquellas, 2012.

[19] The Commissioner of General Intelligence, Rispoli, to the Prefect of Lozère, Mende, April 8, 1943, “Situation politique de la commune de Saint-Alban,” No. 929, RI/YC, Departmental Archives Mende.

[20] Jean Oury, “Préface,” in Tosquelles, Le vécu, pp. 7-11, here p. 8.

[21] The Departmental Director of Police Services of Lozère, to the Prefect of Lozère, Mende, January 13, 1947, “a/s Epoux Tosquellas, sujets espagnols, en instance de naturalisation,” No. 2022, Departmental Archives Mende.

[22] Tosquelles, Le vécu de la fin du monde dans la folie, p. 17.

[23] C.G. Jung, On Psychological and Visionary Art. Notes from C. G. Jung’s Lecture on Gérard de Nerval’s Aurelia, ed. by Craig E. Stephenson, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

[24] Tosquelles, Le vécu de la fin du monde dans la folie, p. 145.

[25] Anne Querrien, «Tosquelles: Madness and Citizenship”, text for the conference “Queer Tosquelles,” 21/22 June 2024, at KHM Cologne, see this issue of transversal.

[26] Tosquelles, Le vécu de la fin du monde dans la folie, pp. 107-126.

[27] Ibd., p. 109.

[28] Ibd., p. 112.

[29] Ibd., p. 113.

[30] Ibd., p. 138.

[32] Tosquelles, Le vécu de la fin du monde dans la folie, p. 153.

[33] Ibd., p. 94.

[34] Nerval, Aurélia, p. 267.

[35] Tosquelles, Le vécu de la fin du monde dans la folie, p. 167.